Shadow Knowledges: On Secrecy and the Communicative State

Mehak Sawhney

“Technopolitics of the Global South" is a modest proposal for naming an aggregator site of new and relevant research that can easily be lost in one disciplinary silo or other. This occasional series on Borderlines inaugurates an effort to connect questions regarding contemporary political forms and practice with numerous other intellectual vectors, of data and digital colonialism, computing from the South, platform imperialism, and mass mediation.

This inaugural dossier begins with introductory framings by Arvind Rajagopal and Francis Cody. This is followed by a set of reflections from Shahrukh Alam, Kajri Jain, Shubhangi Heda and Ishita Tiwary, Anustup Basu, Joyojeet Pal, and Mehak Sawhney.

To every great politics belongs the “arcanum.”

- Carl Schmitt, Roman Catholicism and Political Form.

Contemporary media publicity is marked by a tragic conundrum: how does the otherwise dissenting act of leaking state secrets matter when recorded testimonies and evidence of state violence inundate online platforms? As we scroll through devastating footage from war-torn regions across the world, is there anything hidden, or worth revealing about liberal imperialism, or contemporary settler- and neocolonial state projects? Are innumerable recorded testimonies of violence not sufficient evidence of state crimes? On that account, does Carl Schmitt’s epigraphic dictum to this piece need revision? An answer to these questions can partly be ascertained through a speculative thought experiment: what would an informational world, even today, look without whistleblowers, hacks, leaks, or any access to sources within secretive state chambers? Perhaps irremediable. Evidence of state atrocities from within its arcana or secret rooms – such as the workings of secretive AI platforms in settler-colonies that produce continuous large-scale bombardment sites, or leaked photographs showing torture of political prisoners in detention centres – incriminate the state through its own communicative machinery. While such reflexive incrimination highlights the harrowing devaluation of endless and excruciating victim testimonies, it emerges from a distributed collective of modes and actors, and through tactics (à la Michel de Certeau) for alternative evidentiary claims, until newer means of justice, truth and socio-political reorganization allow an exit from the space-time of the colonial/authoritarian state or global capital.

In such a context, revealing secrets that counter state narratives could be considered significant acts of political action in contemporary times, among other forms of mediated resistance such as recorded testimonies, films, poetry, artworks, and online communities of solidarity. Acts of revealing statist machinations constitute a ‘meso’ realm – between state narratives and victim testimonies – subjecting informational back chambers to some form of publicness. The task of this informational sphere in contemporary times is not necessarily changing the course of political action or eventalizing already spectacular state atrocities, but keeping a duel, albeit asymmetrical, between the state and civil society alive.[1] Making state secrets public, hence, is not as much about revelation of something new as it is about epistemic reorganizations within broader frameworks of resistance that resort to: 1) establishing ‘truth’ through alternative evidentiary modalities, and 2) temporalities that rely not on immediate victories but persistent struggles. Afterall, history teaches us how wars can last for decades and colonialism for centuries, if not forever, and resistance, more often than not, is protracted. Borrowing from the Civil Rights Movement song, Angela Davis would say that “freedom is a constant struggle”, and Ilan Pappé opines that the current condition signals “the last phase of Zionism” that might slowly diminish over the next twenty years.

This piece reflects on the media operations that make visible the arcanum imperii. What kinds of media epistemic practices constitute a leak of secret information for the production of truth? And what dominant affective and knowledge formations do they contest? I map three mediatic ways through which state secrets are made public – intermediaries, traces and counter-forensics – which could collectively be called “shadow knowledges”. These operations do not establish an order of transparency per se, as much as they work as contestations against false claims of iconic/populist leaders, state information and archives, and the ‘fabrication’ of truth and evidence. Truth can be understood in multiple ways – as Foucauldian discursive formations, “factual truth” that Cody explores in this forum, ‘truthiness’ or belief/intuition as an affective feature of the post-truth world, legal frameworks such as inquiry, examination and test, testimonies, and witnessing, among others. The role of media in truth formations has always been central, with historical continuities and discontinuities in the contemporary.

As alternative evidentiary frameworks of producing truth, shadow knowledges can be defined by: 1) procedural recourse to legality – a pharmakon that is both the regime’s apparatus but also a tool for the dehumanized – as a potential site of justice that incriminates the state, 2) the informational realm that sustains a duel between the state and civil society as a domain of political action, 3) an understanding of public information as operating outside the realm of the purely discursive or spectacular, instead defined by the slow work of exposés that keeps some semblance of evidentiary truth alive. Shadow knowledges, as technopolitical instruments of truth, challenge the statist concealment and containment of information, effectuating a redistribution of the epistemological.[2] They do not always pave the way for justice, particularly given the failure of international law in contemporary times. Afterall, of what value is publicizing secret information when state violence is already impunitively public? However, shadow knowledges are epistemic modes of imagining a just future through perpetual resistance. Unlike dominant epistemic forms well documented within the sociology of knowledge – objectivity, paradigms, doubt, and the Foucauldian epistemes – shadow knowledges operate as internal blows of resistance to established structures of knowledge. As internal narratives, past traces, and counter-forensic media question the sacred space of state secrecy, they can create opportunities for what Giorgio Agamben, in a political-theological vein, calls a profanation, that is, conditions when sacred objects (in this case state secrets) are put to a “new use.”

While political theory and political theology have long reflected on the valence of masking, mystery, secrecy and deception as sites of state power, the modern state also materially manifests secrecy, or arcana, through the workings of law enforcement agencies and aggressive surveillance. State secrecy has been understood both through opaque administration and information as well as concealment of political intent. As the mystery and mysticism of state arcana is a media technological operation[3], concerns over surveillance technology in the contemporary world came to the fore most prominently through the Snowden revelations, as well as Julian Assange and Chelsea Manning’s Wikileaks accounts on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The communicative dimensions of the modern state have been studied by scholars such as Bhavani Raman and Matthew Hull, who show how paper (and other media) is central to its structure, functioning and sociality. This structure comprises both subjects and objects – making personal narratives as well as material traces equally significant modes of alternative knowledges. It is the communicative structure of the state – reliant on processes of storage, transmission and circulation – that allows for the leakage of information, making arcana subject to public scrutiny, which Ravi Sundaram describes as “a window into the rearrangements of sovereignty in the posthuman condition.”[4] Given that these theories of revealing state secrets, political accountability, and their repercussions in a rational Enlightenment public sphere are no longer as relevant, what gains significance is the slow resistance of disclosing state secrets that also keeps legal battles active, such as South Africa’s case against Israel in the International Court of Justice, Francesca Albanese’s UN reports that quote a couple of leaks as evidence of recolonization, and multiple bail appeals for the wrongly accused under India’s anti-terror laws, among many others.

INTERMEDIARIES

A significant facet of media publicity in the contemporary is the affective and charismatic presence of right-wing populist figures as they frame state narratives, media events and online circulation of content. Their persona is reproduced across the online world, through organized virality, bots and broadcasting across platforms, modelling algorithms and online trends. While popular discourse is overwhelmed by the presence of such figures as well as right-wing influencers, a slew of whistleblowers – invisible and anonymous producers of counter-state narratives – make so much of investigative journalism possible. Such figures shadow their populist, iconic counterparts, as invisible sources of alternative narratives. These shadow figures exemplify what Michel Foucault calls parrhēsia, free speech that is undertaken for ethical accountability to the self and that might involve the risk of death. While Edward Snowden, Julian Assange, Chelsea Manning, and Deep Throat, among others, are well known figures, whistleblowing is a more common reality than it may seem, making the small but significant world of alternative reportage and truth possible.[5] Another important instance of whistleblowing is the Cambridge Analytica scandal, exposed by Christopher Wylie, who leaked internal documents to The Guardian uncovering the misuse of Facebook data to influence the 2016 US Presidential election and the Brexit referendum.[6]

States (and corporations) have stringent rules for water-tight security of information, and breaches and leaks are a part of their communicative machinery. As a specific historical example, consider rules about typewriter security in India. A 1962 correspondence from the Chief Secretary of the Punjab Government to all the other heads of departments discusses the “Care of Typewriter Ribbons”.[7] The notice details the use of typewriter ribbons, the script of which is “sometimes legible until it has been typed over 4 to 5 times.” Instructions include the reuse of typewriter ribbons to blur script imprints, avoiding red colour for sensitive words, and the use of different typewriters for classified and unclassified material. While the materiality of the typewriter ribbon is a significant security concern, the figure of the typist is an equally worrying one.

In his book A Feast of Vultures, Josy Joseph reflects on the history of modern India through the figure of the intermediary – middlemen, personal assistants and typists. In a chapter titled “The Mighty Typist”, he shares stories about typists and personal assistants of Jawaharlal Nehru, Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi, describing them as figures who knew more about the history of democratic India than anyone else. Elaborating on the role of R.K. Dhawan, the personal assistant to Indira Gandhi when she was assassinated, he says: “The almost silent journey of this typist exemplifies the power enjoyed by hundreds of men and women in India, many of them stenographers, who emerge as men Friday of those in power.”[8] Behind every political leader – “a few steps removed from history”[9] – is a personal assistant. As C.A. Bayly notes in his foundational historical study of surveillance in early modern India, the munshi (secretary) was a central node for circulation of information between British colonial officers and the Mughal courts. In addition to the association of secretaries with gendered labour and early computation, they are also significant behind-the-scenes doorkeepers of secret information. Joseph further shares how Nehru’s personal assistant, M.O. Mathai, shed all loyalty and published his memoirs called Reminisces of the Nehruvian Age in 1978, followed by My Days with Nehru in 1979, sharing his time with the first Prime Minister of India, which detailed multiple scandals, including his long affair with Indira Gandhi.

The genre of the memoir is an important, albeit partial, source of information for visible-izing state secrets and the functioning of the government. There is a whole parallel industry of books by retired bureaucrats, police officials and other officers that fall under the genre of exposés. Local publishers in Delhi and elsewhere – such as Manas and Lancet Publications – produce memoirs by retired bureaucrats as well as police and defence personnel. With its motto being, “we convert fighters into writers”, some of the books published by Manas include titles such as: Police: What You Don’t Know, CBI Insider Speaks: Birlas to Sheila Dikshit, A Bureaucrat Speaks, CBI HQ: Victory of Mystery, among others – generating literary intrigue and revealing state truths in equal measure (Figures 1 and 2). Books by the former data analyst and consultant for the BJP, Shivam Shankar Singh, which detail the party’s reliance on data analytics for campaigning, also fall in the same genre.

Figures 1 and 2: Book catalogues by Manas Publications, Daryaganj, Delhi. Images by author.

Many typists, secretaries, bureaucrats, intelligence officers, and data analysts, across the world play a central role in making state secrets public. Not all attempts are successful. In the corporate world, the OpenAI whistleblower Suchir Balaji, who had evidence of the company’s copyright violations, was found suspiciously dead in his San Francisco apartment last year. In India, a judicial commission dismissed testimonies and evidence by three whistleblowers implicating Narendra Modi and other state officials in the 2002 Gujarat riots, one of whom has been sentenced to life imprisonment. These cases, however, point to the informational threat whistleblowers pose to both corporations and states.

TRACES

State archives and databases are artifacts of containment that are intrinsically leaky, and sometimes unpredictably so. Jacques Derrida associates the archive with the death drive and erasure as well as with future-oriented reinterpretations: “The archive: if we want to know what this will have meant, we will only know it in the time to come.” Archival and media traces of the state’s crimes and operations within its communicative apparatus often surface arbitrarily, at times through counter-forensic interventions, at others as accidental disclosures. A recent unintended disclosure was the SignalGate scandal – where top US officials including Michael Waltz, Marco Rubio, Tulsi Gabbad, J.D. Vance, and others – were part of a Signal group with disappearing messages discussing plans for Operation Rough Rider that entailed air and naval strikes against the Houthis in Yemen. The inadvertent inclusion of Jeffrey Goldberg, The Atlantic’s editor-in-chief, in the group revealed not only US military plans but also the fact that top US officials were using Signal instead of secure government channels for communication, perhaps to “evade transparency laws through the illegal destruction of government records.”

A pivotal moment in the Bhima Koregoan-16 case in India – where 16 activists were arrested under India’s anti-terror law based on fabricated evidence – exposed links between email accounts of three imprisoned activists and a Pune police officer involved in the case. SentinelOne, a cybersecurity organization, found that compromised email accounts had their recovery email set up as a backup mechanism, which had the full name of a Pune police official who was closely involved in the case. This counter-forensic investigation revealed a trace left behind by either the hacker or the officer involved, linking the hacking of accounts with the Pune police, implicating the state in falsely accusing those it had arrested under anti-terror laws. In her reading of Walter Benjamin’s account of photographic traces, Carolina Carvalho says that “the photographic image is historical not when we see in it an accurate image of the past, but when it breaks with the continuum of history.” Media traces of state violence offer such breaks from the state’s historical and contemporary narratives.

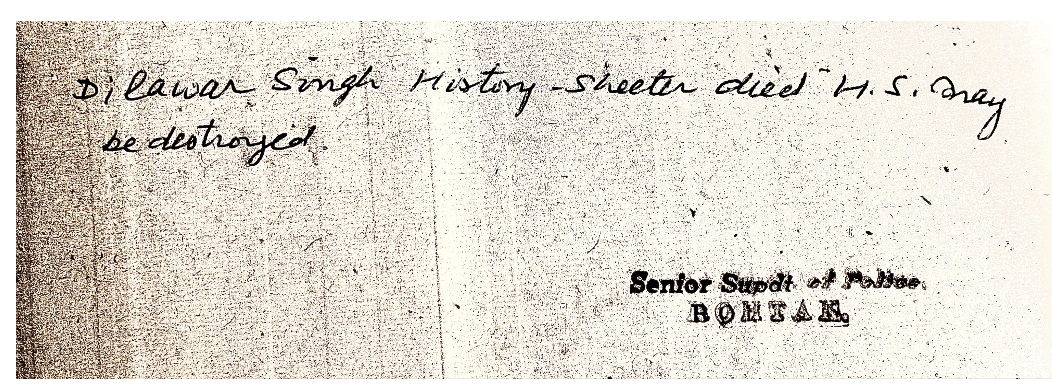

In addition to disturbing official accounts through counter-forensic operations, a facet I will discuss in the next section, traces are also material remnants that emerge in serendipitous and unintended ways. During my archival research on surveillance practices in postcolonial India, I came across multiple files of surveillance that were meant to be destroyed (Figure 3). Profiles of ‘suspects’, intercepted letters and many other surveillance records were available decades after they had been ordered to be destroyed, offering post hoc diachronic insights into such practices. Sometimes institutional decisions of de/classification also facilitate deferred counter-historical windows into analyzing state actions. Anthropologist Katherine Verdery provides a fascinating insight into her Romanian Securitate files, which were declassified after 1989, alongside her fieldnotes from the region, sifting thought her many “selves” and thinking “to what extent ethnography…necessarily makes one a kind of spy.”[10]

Figure 3: “Dilawar Singh History Sheeter died. H.S. [History Sheet] may be destroyed.” Haryana State Archives, Panchkula.[11]

State documents and records are also frequently burnt or evaded, given the culture of informality and orality in bureaucracies. During an interview with a lower-level official who worked as a technician and eavesdropper in India, I was shown multiple phone-tapped recordings on their WhatsApp that had no official documentation and were conducted as personal favours for senior officers. They told me they had them saved in case they were questioned in the future: traces exist in multiple forms, many a times exceeding bureaucratic cultures of orality and erasure.

Other instances of material traces include archaeological or physical remains – for instance mass graves built during the Nakba in Palestinian villages or those found beneath residential schools in Canada – or forms of nonhuman witnessing that exceed state records.[12] Thinking about the wildfires that broke out in the southwestern hills of Jerusalem in 2021, Sherena Razek discusses the terraced vista that emerged from beneath the settler pine plantings, revealing Palestinian relationships with the land. Traces – archival and material – erupt in ways that constantly question contained and secret state arcana.

COUNTER-FORENSICS

The history of modern forensics is closely associated with colonial practices of criminology and eugenics, widely reproduced through carceral techniques of exclusion in Western democracies and postcolonial states alike. Counter-forensics “is a civil practice that seeks to invert the institutionalized forensic gaze, with individuals and organizations taking over the means of evidence production, and turning the state’s means against the violence it commits.” Notably deployed by the activist and art institution, Forensic Architecture, counter-forensics makes the publicity of media content – recorded by the crowd and openly available – the condition of its investigations, bypassing access to the state’s arcana. In the words of Eyal Weizman, “We thought that we could expose secrets simply by learning again how to look at the material that is anyway out there.” The openness of media publicity in the last fifteen years has thereby also led to legal counter-forensic analysis in support of liberation struggles against state crimes. In addition to Forensic Architecture, counter-forensic investigations are also practiced by a range of other organizations such as Amnesty International, Bellingcat, SentinelOne, and the Citizen Lab, among others.

A major counter-forensic breakthrough in India took place recently in relation to the BK-16 case, where activists, journalists and forensic organizations produced reports on how the evidence of the BK-16’s arrest – primarily ten fabricated letters – were planted on the devices of the accused Rona Wilson and others in a sustained decade-long hacking attack on their digital devices. Similarly, The Citizen Lab, an interdisciplinary investigative lab based at the University of Toronto, has been involved in producing counter-forensic reports on the use of mercenary spyware, particularly Pegasus, by the Israeli company NSO, by states across the world. Among the most well-known cases they addressed was the Saudi Arabian journalist Jamal Khashoggi’s extrajudicial murder due to spyware surveillance on his wife’s phone. Counter-forensics challenges not only state forensics, but more importantly, fabricated narratives and evidence by the state. Israeli narratives of “self-defence,” fabrication of post-mortem reports of the forcefully disappeared from Syria to Kashmir, doctored and deepfake videos by ethnonationalist sources, and the everyday manipulation of evidence for high- or low-profile cases in India and elsewhere – are all ways to “fabricate” reality. Practices such as fact checking are also responding to this contemporary post-truth episteme of ‘fabrication.’

Mayur Suresh reflects on the fabrication of accusations and evidence in his book Terror Trials, and how the wrongly accused gradually learn “legal technicalities” and procedures to prove otherwise. The fabrication of truth – through political speech, online content, fake evidence, and even false or deliberately partial scientific studies – are a facet of everyday political life across contexts. While associated with Trump’s first election and the Brexit moment, post-truth is more a phenomenon of intensification in the contemporary than a complete political rupture. It is not a novel phenomenon merely associated with synthetic media such as editing software, deepfakes, or generative AI. As Suresh’s work shows, files and certification as media forms central to the fabrication of false cases against Kashmiris, Muslims and Dalits has always been a media epistemic modality of legal governance.

As an epistemic phenomenon, fabrication misuses the centuries long history of media indexicality as evidence. While media indices have been critiqued because media are always socio-politically constituted, the current crisis in media truths emerges from both their synthetic and fake production as well as networks of circulation where they acquire completely newer meanings detached from their moment of production, as explored by Cody. Such a crisis of the indexical is dangerous as it is appropriated by the state to deny culpability, and by media consumers who believe something to be true not through indexical value but ideological positions, also called truthiness – a video depicts true events if the viewer ‘believes’ they are true. This reveals a form of knowing where ideology precedes fact or even affect.

As another example – consider the current crisis in the representation of numbers. False COVID data, deceptive environmental assessment reports with fabricated studies, concocted graphs of economic progress that circulate on social media – add another epistemic and affective layer to the histories of quantification, statistics and “trust in numbers.” Numbers here are engineered signs without any objects as their referents. While signs in late modernity have been analyzed for their attachment to commodity culture, in the case of state fabrications, signs are pure ideology – language, numbers, images are framed and perceived along deeply ideological lines.

Counter-forensics and other practices of revealing truth respond to this crisis of indexicality as the vector of truth. As Weizman explains, counter-forensics reveals other modes of truth-making, where the materiality of the medium, in addition to its representational qualities, becomes a vector of establishing presence or evidence. The relationship between sign and event here changes, and Benjamin’s optical (or medial) unconscious takes on newer material lives geared towards justice and liberatory struggles through storytelling, animation, and evidence in court and other fora.

CODA

Intermediaries, traces and counter-forensics, all emerge as alternative evidentiary practices out of the communicative structure of the state, profanations that put state secrets to a new use. They are parallel, shadow formations, challenging claims to truth by political figures, state archives and fabricated evidence. While these profanations do not result in a complete reorganization of the social or the political, they do point to existing modes of (privileged) interventions in times when other forms of truth making are rendered highly insignificant, even more so when publicity is characterized by algorithmically produced echo-chambers. Shadow knowledges are not necessarily spectacular or teleological, but slow and contingent modes of epistemic reorganization that keep the duel between the state and civil society alive and operate within longer struggles of epistemic resistance. They are dissident anti-archives – non-institutional and scattered – of the state’s crimes written in its own ink, awaiting a popular verdict in a people’s tribunal. As Esmat Elhalaby notes, “In the face of genocide, we must imagine, in the stead of those Palestinians who have struggled for years, the opposite of genocide.” That opposite perhaps is a proliferation of life and liberation and an incrimination of colonizers and states in equal measure.

Endnotes

[1] I use the term ‘civil society’ with caution, given its critique as an inadequate framework to address varying forms of sociality in postcolonial contexts, or its difference with ‘publics’ that are self-organizing political entities. See Francis Cody, “Publics and Politics,” The Annual Review of Anthropology 40 (2011): 37-52. For more on the relationship between state secrecy and civil society see Howard Caygill, “Arcanum: The Secret Life of State and Civil Society,” In The Public Sphere from Outside the West, edited by Divya Dwivedi and Sanil V (London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2015), 21-40. Caygill argues, as also pointed out by Cody in this forum, that the secrecy of the state and the surveillance of the civil society work in conjunction, and the latter need to build an arcanum of their own to undertake any form of radical politics in the age of digital technology, contrary to the “Öffentlichkeit or open space of civil society.” Caygill also contests the state-civil society relationship as that of a Clausewitzian duel, arguing that both parties operate as anti-political entities: the state due to its pursuit of war and manhunt (as opposed to providing a level playing field), and the civil society due its commitment to morality. I, for the purposes of this piece, use the idea of the ‘duel’ as a partial but useful framework to think about acts of communicative resistance – not as an encounter between equals but as the continuing existence of and perilous investment in anti-colonial and anti-fascist struggles.

[2] I am using ‘shadow’ as an adjective in a somewhat Rancière-ian sense, – for instance, as it is used to describe shadow libraries – operating as a mode of access and revelation of knowledge/information against structures of containment, concealment and secrecy central to the communicative state. This understanding changes the parametres of what is knowable/audible/seeable as ‘truth’.

[3] A significant component of understanding the communicative practices of the state has been about processes of subjectification through surveillance technologies such as biometrics, identity cards, fingerprinting, and photography that have taken data-driven forms of face recognition and dataveillance today. Other forms of surveillance include territorial and military surveillance that establish its control over territory as much as subjects. This piece, however, aims to focus on the communicative structure of the state, and not its media technological dimensions of control. It highlights how this communicative structure is a condition of possibility for leaks, traces and counter forensics that visible-ize the arcanum.

[4] Ravi Sundaram, “Leaks and Stings,” In Posthuman Glossary, edited by Rosi Braidotti and Maria Hlavajova (London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018), 232.

[5] For more on the politics and cultures of hacking, see Gabriella Coleman, Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: The Many Faces of Anonymous (New York: Verso, 2014); Gabriella Coleman and Christopher Kelty, eds, “Hacks, Leaks, and Breaches,” Limn 8, February 2017.

[6] See Carole Cadwalladr, “‘I made Steve Bannon’s Psychological Warfare Tool’: Meet the Data War Whistleblower,” The Guardian, 18 March 2018.

[7] Haryana State Archives, Deputy Commissioner Confidential Records, Karnal, Accession Number: 8099.

[8] Josy Joseph, A Feast of Vultures: The Hidden Business of Democracy in India (Noida: HarperCollins Publishers, 2016), 42, 50.

[9] Ibid, 42.

[10] Similarly, Maya Wind’s ethnographic and archival study of how Israeli higher education is tied to the state’s security apparatus has also been called “a powerful exposé.” See Maya Wind, Towers of Ivory and Steel: How Israeli Universities Deny Palestinian Freedom (New York: Verso, 2024).

[11] Haryana State Archives, Rohtak SP, Accession Number 8842.

[12] For more on nonhuman witnessing, see Susan Schuppli, Material Witness: Media, Forensics, Evidence (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2020); Michael Richardson, Nonhuman Witnessing: War, Data, Ecology after the End of the World (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2024).

Mehak Sawhney is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Media Studies, University of Colorado Boulder. Her research interests include sound and media studies, surveillance studies, and the environmental humanities.

Thumbnail Image: by the author