Ajay Skaria opens up a conversation on presentism in historty for Borderlines: Skaria writes: “to get to the historical approach as a—the—modern regime of historicity, it helps to revisit the classic distinction between the judge and the historian. Since Marc Bloch, we have often thought of the juridical as engaged in the act of judging and the historical as engaged in the act of understanding. This is correct, but it is still too preliminary a way of putting matters. As Carlo Ginzburg, Ranajit Guha, and others have shown, historians also usually act as judges—for example, in deciding on the veracity of their sources or in privileging a certain narrative over others”.

Read MoreSharad Chari responds to Skaria from the viewpoint of a geographer: Chari writes: “I am therefore convinced alongside Skaria that the ‘presentism’ debate could benefit from reflecting on its conditions of possibility. I hope to have offered Marxist fodder for this task. Marxist social historians and geographers, at their best, have tended to keep their critical insights to absolute space and time and relative space-times. But several dissident Marxist traditions have also offered insights that bring the genealogical and what Skaria calls the historial into the frame, but in relation to the diagnosis of absolute and relative spacetimes as well”.

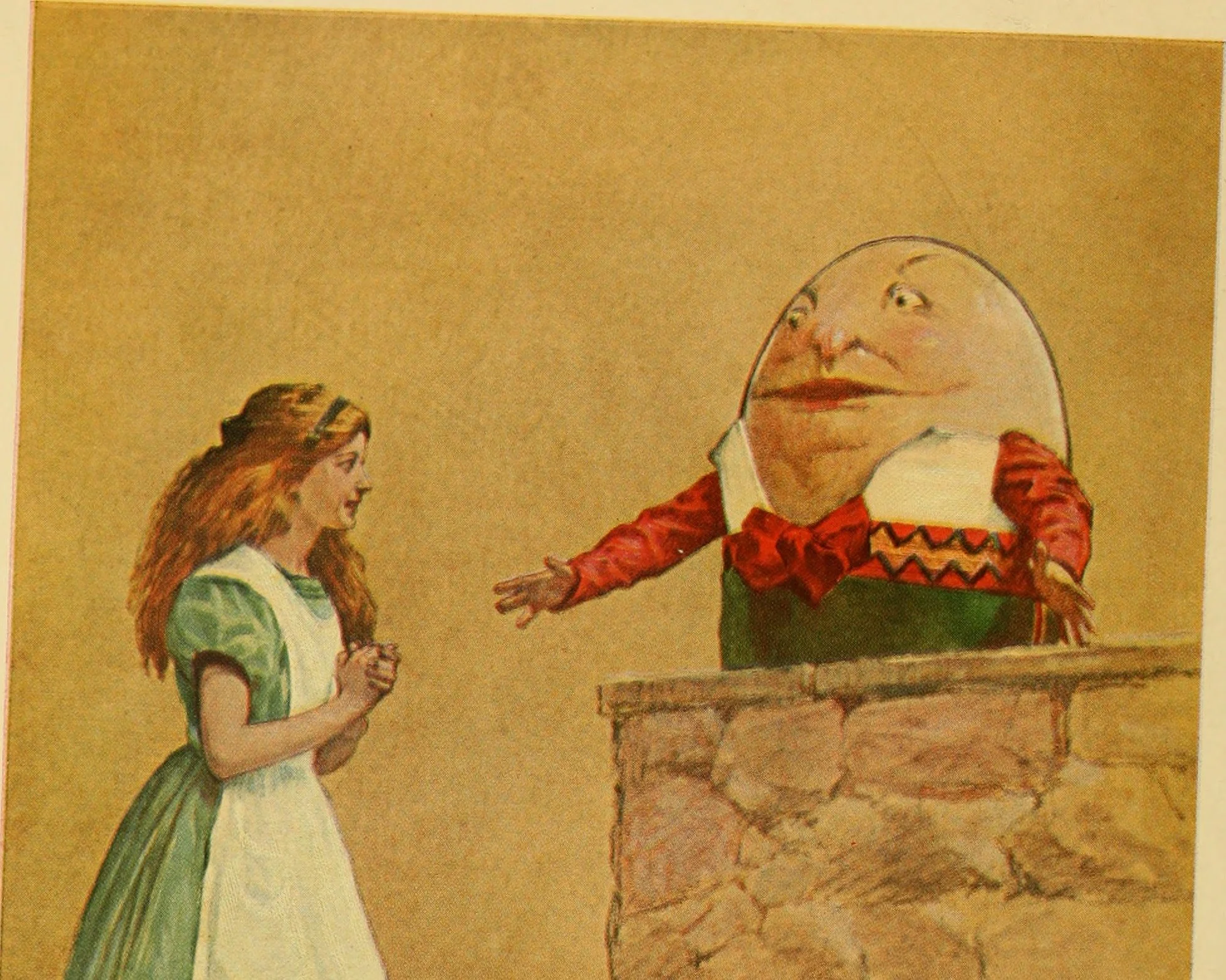

Read MoreMichael E. Sawyer responds to Skaria; Sawyer writes: “the feeling of intellectual utopia troubles me here and is the motivation for the title. Some people want a Wonderland without Alice to take us there and translate it for our understanding. Isn’t that the point of Lewis Carroll’s work? That Wonderland is only wonderful because it is viewed in relation to the world that Alice visits from otherwise it is just “Land” qua itself. Incidents of historical moral depravity are not isolated and only to be properly understood vis-à-vis the moment in which they occur because, and here I’m reluctantly returning to Maher, the reason he stashed the gum in his pocket rather than take it to the cash register is because he knew then as he knows now that what he was doing was wrong”. Read more here.

Read MorePatricia Hayes adds to the conversation, drawing from photographs and images. Writing on the image excerpted on this thumbnail, Hayes writes: “This photograph [Fig. 1] appears to inscribe, or record, a formal occasion–what seems almost a ritual practice–to mark the moment a new sovereignty came into being. This followed two military campaigns, the first in 1904 a disaster. In the album I studied in Luanda, Angola, the caption for the Portuguese photograph in 1907 holds a set of specific references, in terms of the protocols of capitulation, for it was termed as: auto de vassalagem, or act of vassalage, a term associated with feudalism. What does this vestige of feudalism in the Portuguese nomenclature imply? I ask this because this particular periodization break tends to clump things: it sets up the medieval/feudal against the modern/commercial or capitalist.”

Read More