Response III: “Presentism? Democracy between the historical, genealogical, and historial"”

Patricia Hayes

A central aspect of Ajay Skaria’s response to James Sweet’s criticism of “presentism” centers on the recuperative project of historical writing, that straining towards addressing absence and “making things fully present.” Skaria’s point has been argued many times, that these efforts are only made thinkable and replete with tantalizing possibilities when one operates from a basis of a naturalized conception of empty homogenous time.

The argument about “making things fully present” calls to mind a fertile play on words by art historian Georges Didi-Huberman. Regarding the image, he touches on an equally problematic expectation that we can “decode the world.” This vanity is another kind of assumed sovereignty. The term in French for decode is déchiffrer, often translated as “decipher.” But in a subtle alteration of vocabulary, Didi-Huberman insists on the necessity to also déchirer, that is, “to tear” the world.[i] This tearing, says Laurent Zimmermann, is the “otherwise essential experience of the visual coming towards us to upset the configurations of knowledge that usually confine us.”[ii]

As one of a growing number of scholars attempting to work with history and images, specifically photographs, the way such images might “upset the configurations” offers a productive entry point into the conversation about history, historicism, violence and the global instated by Ajay Skaria. For there is an “idealized sense of distance favored by the historian” that photographs trouble in very particular ways and which has generated a rich body of thought. Jennifer Tucker insists that photographs pose questions “that are equally applicable to other sources.”[iii] Elizabeth Edwards in turn highlights their propensity to puncture certain assumptions upon which the discipline is based. It is particularly the instabilities thrown up around time that I wish to highlight, for as Edwards has repeatedly argued, with photographs, time does not work in a linear way.

Photographs demand a different and multiple conception of time that challenges assumed linearities, resisting Newtonian conceptions of inevitable linear time as an adequate explanatory framework for the temporal complexities they offer, and indeed represent. They reproduce, overlap and fold back time. They offer temporal experiences that work in circles, rhythms, pulses, folds and ripples. These collide, spill, jolt and swirl in ever shifting sets of relationships, constituting and reconstituting the past and its relationship with the present.[iv]

While all historical sources present us with dilemmas of seeing or reading something from the past in the present, it is the way a scene in front of the camera has been visually inscribed that “makes them of a different order.”[v] The key term here is inscription, which retains its sense of immediacy through time.[vi]

Probably the most cited meditation on photographs and temporality is Roland Barthes’ formulation of the “illogical conjunction of the here-now and the there-then.”[vii] The poignancy and intimacy of his tone in Camera Lucida, the sense of being “wounded” as if by an arrow from the past when confronted by what is lost to the viewer in the present, its play on the transmission of real time (“‘I am looking at eyes that looked at the Emperor’”),[viii] have captivated generations. While it has its productivities, Barthes’ affective dimension has been criticised for its blanketing over of certain anxieties, especially race.[ix]

Of course, there are further temporal questions that arise when considering how–and when–they come before us in the present, or at different “present” points, those multiple reconstitutions, as Edwards puts it, of different “scales and actions.” But we are confronted in very specific ways by the way time is organised in photographs of things past, and I wish to remain with this aspect for the moment: time as inscribed in the photograph. This is pertinent especially when working with older photographs where affective responses, attempts at decipherment or narrative integration often splinter into multiple directions.

Here the 1927 essay on photography by Siegfried Kracauer remains very pertinent, where he uses photography to critically consider historicism and its presuppositions about time. For instance he writes: “Photography presents a spatial continuum; historicism seeks to provide the temporal continuum. According to historicism the complete mirroring of a temporal sequence simultaneously contains the meaning of all that occurred within that time.”[x] According to this logic of total decipherment, if anything was missing–an absence– it would lack reality.

Memory works differently, according to Kracauer, it retains only what is significant. From that perspective, “photography appears as a jumble that consists partly of garbage.”[xi] Even more suggestively, he suggests that in its radical optical inventories, photography “stockpiles the elements.”[xii] It follows then, that “the photograph captures only the residuum that history has discharged.”[xiii] Instead of being “pierced” or “pricked” as Barthes would have it, Kracauer’s viewer of old photographs undergoes a shudder. “For the photograph does not make visible the knowledge of the original but rather the spatial configuration of a moment; it is not the person who appears in his in his or her photograph but the sum of what can be deducted from him or her.”[xiv]

Then, in an extraordinary motif, Kracauer notes: “In a photograph, a person’s history is buried as if under a layer of snow.”[xv] Blanketed under the “metrical accuracies of the camera,”[xvi] it is as if the weight of materiality in the human/nonhuman interface that is photography covers the subject in a kind of climactic fallout. As Ajay Skaria reminds us, the subaltern cannot speak and should not be made to speak.

I have cited this at length because it is a salutary reminder that what we might expect to find in photographs is not evidence, but elements. And sometimes these elements “perforate the self-evidence of the world.”[xvii] That “sum of what can be deducted from him or her,” that residue, is but a vestige. In Images in Spite of All, whose term “all” suggests a pressure on the dialectic or arriving at an absolute system, Didi-Huberman urges that we attend to those remnants for they undermine any sense of allness or entirety. As John Ricco observes, this points us in the direction of a non-redemptive image.[xviii]

Such a direction has marked my own work in southern Africa, which draws on photographic archives from the early twentieth century. I will dwell briefly on one instance, from a specific moment of the inception of colonial rule on the border between Namibia and Angola in southwestern Africa. My initial inquiry concerned what happens when previously autonomous people came under administration (called Native Administration) for the first time. This arises from a larger preoccupation with what existed there already, and how this played out when formal non-African presences and rules were established. My interest was not confined to the spatial but encompassed the assumed temporal break as well. This was to insert a question where there is normally an uninterrogated borderline between “precolonial” and “colonial” in African historiography, and thus also interrogate the workings of history. This inquiry, therefore, addressed two sovereignties: that of colonial occupation and that of the historian.

Unlike the thick records available across the border on northern Namibia (German and South African), reports and other materials for the Portuguese side in southern Angola are very thin. Confronting this dearth, and as a last resort, I recalled that there was a photograph of the official transfer of sovereignty in the Mbandja kingdom to their Portuguese occupiers in 1907 –the so-called rebellious Cuamato–the nearest visual record of a process I refer to as “inception.”

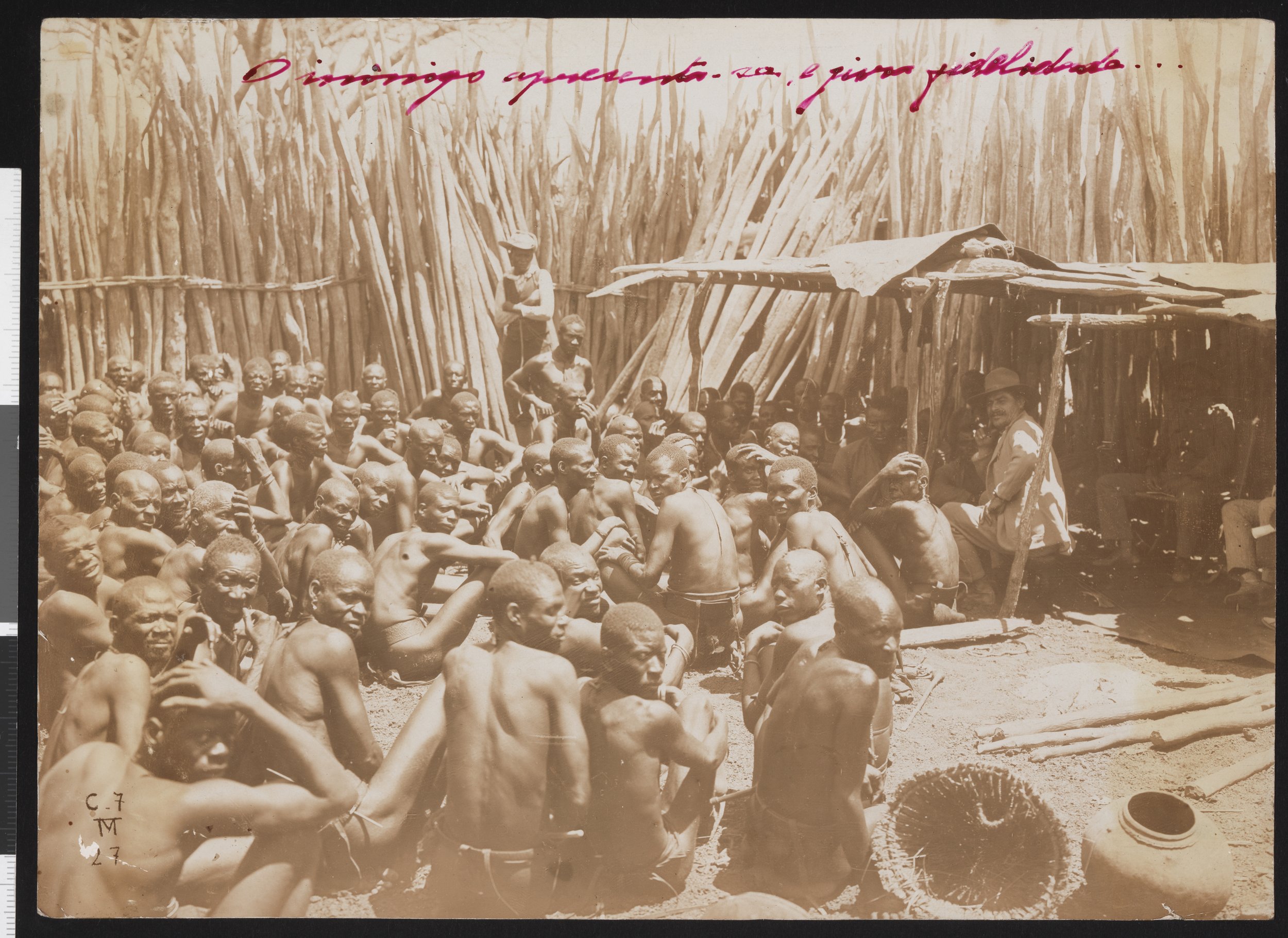

Fig 1: ‘The enemy comes forward, and swears allegiance ...’ [Auto de Vassalagem].

Sourced here from: José de Almeida “Pesca-Rãs” (1907-1907), “Campanhas do Cuamato de 1907”, Fundação Mário Soares / Documentos Carvalhão Duarte/Rocha Martins, Disponível HTTP: http://www.casacomum.org/cc/visualizador?pasta=04498.006.040.001 (2022-11-28).

This photograph [Fig. 1] appears to inscribe, or record, a formal occasion–what seems almost a ritual practice–to mark the moment a new sovereignty came into being. This followed two military campaigns, the first in 1904 a disaster. In the album I studied in Luanda, Angola, the caption for the Portuguese photograph in 1907 holds a set of specific references, in terms of the protocols of capitulation, for it was termed as: auto de vassalagem, or act of vassalage, a term associated with feudalism. What does this vestige of feudalism in the Portuguese nomenclature imply? I ask this because this particular periodization break tends to clump things: it sets up the medieval/feudal against the modern/commercial or capitalist.[xix]

Moreover, what does this act of vassalage look like? A host of bodies (over sixty) were gathered around a small group of Portuguese under the shaded area, all packed into a small space inside the palisaded embala (palace). Many seem to have turned their heads towards the camera in the time it took for the photographic inscription to be made upon the sensitive emulsified plate. Some were looking off to the side, as if there were multiple lines of direction or instruction around the group, a kind of surveillance on the outside. This was not a public, but an audience. What is frightening is how little we can know about it, who they were, what exactly was going on, even in relation to other records. As viewers we stand on a threshold that allows only partial visibility, peering into a scene from 1907. It is both microtemporal and somehow monumental, the signs of its making hidden, only the gestures of turning heads to suggest a choreography or some kind of unity. This is the residue, Kracauer’s “jumble” that is sealed into the image. Such limited “conditions of knowability” often mark the effort to work with photographs, “rather than a clear methodology or evidential form.”[xx] There is an important injunction to seize on that limit however, for “it points us in certain directions.”[xxi]

The Portuguese photo and its caption set me on a path of reading that suggested something fascinating about periodization/s and the complexities of colonial expansionism in relation to the internal turmoil of a country or region becoming a nation. This has to do with becoming sovereign over oneself. The first clue was the term, auto de vassalagem. Does it mean the Portuguese were still feudal? In terms of their colonial rule this has been hotly debated, and the term largely dismissed as misleading. According to Beatrix Heintze however, the specific ritual of the auto de vassalagem was implemented from the sixteenth century and continued for an astonishing length of time despite its long obsolescence in Europe, and was only discontinued in Angola in 1920. It came with a set of agreements that also remained fairly consistent: political loyalty, military and other labour service, and taxation, often a so-called war tax to pay for the campaign that subjugated the people in question.[xxii]

And here I return to the question of periodization and sovereignty, where Kathleen Davis contends that the concept of feudalism was invented at the moment of its passing, in order to distinguish Europe from its past, from the Middle Ages, and from its elsewhere, like India, and the Americas. She writes, “The redefined humanity so crucial to colonial rule and to the logic of empire also depended upon a reworked, embattled identification of and with a European ‘past,’ which was articulated in minute detail yet superseded by a historiographical idealism that ultimately bonded–in the breach, so to speak–the ‘Middle Ages’ and the colonial subject.”[xxiii] By repeatedly enacting a “feudal” gesture on African soil, what is being encrypted by the Portuguese, apart from putting people into another time?

The contents of the Cuamato photograph might be opaque, “buried under a layer of snow,” but the image exists for a reason and was intended to mediate what then becomes “history.” The only way to represent this was by “cutting into time, slicing it in such a way that it could become representable.”[xxiv] It is then “archived in its discontinuity.”[xxv] This gesture must have a bearing on the cut of periodization. Right here we have the attempt to produce the “laggards in their place in abstract and homogenous time” and the violence that, in Skaria’s analysis, is justified by this problematic construction of time.

Patricia Hayes, Ph.D., is a distinguished professor at the University of the Western Cape, where she focuses on African History, Gender and History, and Visual History. Specializing in colonial and political photography in Southern Africa, her research explores the nuanced narratives of Namibian history and the broader implications of visual documentation in historical contexts. Born and raised in Zimbabwe, Hayes earned her Ph.D. from Cambridge University in 1992, focusing on the colonization of northern Namibia and southern Angola. Hayes is leading the Visual History research project at the University, emphasizing Southern African documentary photography, further contributing to the academic exploration of visual culture in historical studies. Among her notable accolades, her work "The Colonizing Camera" was shortlisted for the Sunday Times Alan Paton Award in 1998.

-Prepared with the editorial assistance of Charles Milne-Home

endnotes

[i] Georges Didi-Huberman, Essayer Voir (Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 2016), 10.

[ii] Laurent Zimmermann, ed. Penser par les images: autour des travaux de Georges Didi-Huberman. (Nantes: Éditions Cécile Defaut, 2006), 7.

[iii] Jennifer Tucker, “Entwined Practices: Engagements with Photographs in Historical Inquiry,” History and Theory, 48, 4, December 2009, 4.

[iv] Elizabeth Edwards, Photographs and the Practice of History (London: Bloomsbury, 2022), 32.

[v] Edwards, Photographs, 32.

[vi] Edwards, Photographs, 33. Inscription here is preferred over the concept of index.

[vii] Roland Barthes, “The Rhetoric of the Image” in idem, Image Music Text (London: Fontana, 1977), 44.

[viii] Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida (London: Vintage, 1993), 1.

[ix] Fred Moten, In the Break (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 205.

[x] Siegfried Kracauer, “Photography,” Critical Inquiry 19, 3 (Spring 1993), 425.

[xi] Kracauer, “Photography,” 426.

[xii] Kracauer, “Photography,” 428.

[xiii] Kracauer, “Photography,” 429.

[xiv] Kracauer, “Photography,” 431.

[xv] Kracauer, “Photography,” 428.

[xvi] Allan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive” in Richard Bolton (ed), The Contest of Meaning (Cambridge MA: The MIT Press, 1996), 353.

[xvii] Georges Didi-Huberman, “Critical Image/Imaging Critique,” Oxford Art Journal 40, 2, (2017), 254.

[xviii] Georges Didi-Huberman, Images in Spite of All (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2008). Thanks are due to John Paul Ricco, Global Classroom discussion, 2 February 2022.

[xix] Kathleen Davis, Periodization and Sovereignty (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008), 3. The original photograph I encountered with the caption “Auto de vassalagem” was at the Centro Nacional de Documentação e Investigação Histórica in Luanda, now the Arquivo Histórico Nacional. The caption inscribed in the print reproduced here from the digital repository of the Mário Soares Foundation in Lisbon translates as “The enemy presents himself to swear loyalty….”

[xx] Edwards, Photographs, 33.

[xxi] Edwards, Photographs, 47.

[xxii] Beatrix Heintze, “Luso-African feudalism in Angola?”, Revista Portuguesa da História XVIII (1980), 111-131.

[xxiii] Davis, Periodization, 34.

[xxiv] Mary Ann Doane, “Temporality, Storage, Legibility: Freud, Marey, and the Cinema,” Critical Inquiry 22, 2 (Winter 1996), 325.

[xxv] Ernst van Alphen, Failed Images (Amsterdam: Vis-à-Vis, 2018), 265.