A Cosmovisión of Solidarity: Anticolonial Worldmaking and the Politics of Possibility

Borderline inaugurates the first essay in its Worldmaking forum on the politics of anti-colonial solidarity across and beyond the Middle East.

Sorcha Thomson

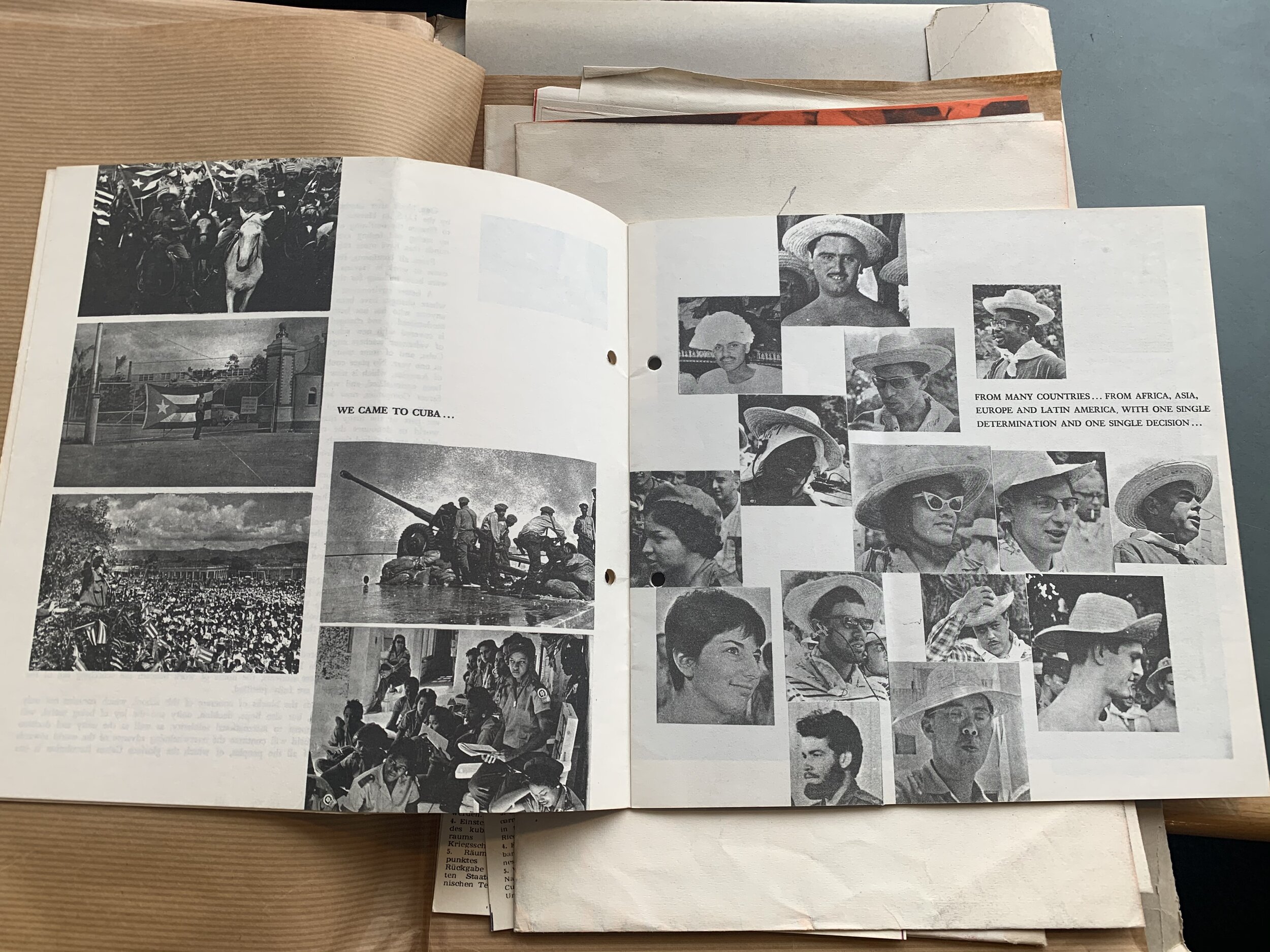

Pamphlet from the 1961 international student camp in Havana and part of Cuba’s campaign against illiteracy during the ‘Year of Education’.

In June 1961, as part of the campaign against illiteracy during Cuba’s ‘Year of Education,’ a delegation of young people and student leaders from 43 countries arrived in Havana to build a school for the children of Cuba. The Cuban Federation of University Students (FEU) received representatives from student unions across the Arab world – from Lebanon, Iraq, Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco – alongside their comrades from Africa, Asia, Latin America, and Europe. The brochure marking the event, titled ‘Cement, Water, Sand, and Unity,’ articulated the students’ reactions to the transformations occurring on the revolutionary island: “The whole of Cuba is a beehive, where changes have been made in two years of Revolution which seem unbelievable to anyone who has not been able to see them personally.”

Two years earlier, on 1 January 1959, the triumph of the Cuban revolution shook the world and ignited the revolutionary transformations of an era – making possible what before had seemed impossible: the defeat of imperialism through popular struggle. In the following decade, Havana would become a hub and a school for tricontinental revolutionaries from Africa, Asia, and Latin America – a place where colonialism’s ‘rule of difference’ was contested through new ways of doing and imagining solidarity across continents. Cuba’s transnational role in this period has been understood in relation to the diplomatic dynamics of the Cold War, with its support for national liberation struggles viewed as defined – and limited – by Soviet foreign policy. Yet, Cuba acted as a key pillar in the transnational networks of thought and action that connected the revolutionary movements of the era – as a model and an actor in an anti-colonial struggle. The island became a hub for the traveling revolutionaries of that time period, who came together at landmark meetings and moments to develop relations of collaboration, mutual support, and friendship, in their efforts to build a world beyond imperial division.

In this way, Havana emerged as a global city of anticolonial worldmaking. An integral part of its worldmaking extended to the liberation movements and the revolutionaries of the Arab world and, in particular, the Palestinians at a time when, in the words of Karma Nabulsi and Abdel Razzaq Takriti, the Cuban revolution was to Latin America what the Palestinian revolution was to the Arab world. These iconic movements of the 1960s and 1970s, each holding a special place in the anticolonial imaginary of the global Left, developed strong mutual relations of support and revolutionary exchange. Located within the revolutionary entanglements of Cuba and Palestine are forms of solidarity – in student, cultural, and women’s forums and international organizations – that created lasting institutional and affective ties. These forms of solidarity reveal the transformative practices of a Havana-based anticolonial worldmaking, characterized by building solidarity across boundaries and a shared belief – in a historical moment of hope – in the possibility of a future beyond imperial domination.

Cuban Internationalism: A Tricontinental Infrastructure

From the outset, the Cuban revolution set about building the institutional framework for developing its diplomatic and cultural relations with the tricontinental world. The publishing house-cum-cultural institution Casa de las Américas was established in April 1961 with the aim to disseminate Cuban culture, literature, and ideas to audiences across Latin America, the Caribbean, and the rest of the world. The Cuban Institute of Friendship with the Peoples (ICAP), founded in December 1960, had the explicit purpose of facilitating and organizing reciprocal links of solidarity with the different regions of the world. Alongside the other instruments of organization developed on the island in the early years of the revolution, these institutions set the foundations for a structured model of international solidarity with broad popular participation.

Havana confirmed its place in the heart of the Third World imaginary when it hosted the January 1966 Tricontinental conference. Hailed as the largest gathering of anti-imperialist leaders the world has ever seen, more than 500 representatives from national liberation movements, guerrilla groups, and independent governments of 82 countries, including a PLO delegation, gathered to discuss anti-imperialist strategy, resulting in the founding of the Afro-Asian-Latin-American Peoples’ Solidarity Organisation (OSPAAAL). The meeting announced itself as the coming together of two historic currents of world revolution – that which started with the 1917 Russian Revolution and the parallel current of the revolution for anti-colonial national liberation. The USA State Department, deeply concerned by this coming together, denounced the meeting as the “biggest threat that international communism had ever posed to the free people of the world.”

This landmark event celebrated Cuba’s role as an icon of revolutionary victory while recognizing the challenges that lay ahead for the global anti-colonial struggle. Che Guevara’s Message to the Tricontinental – delivered to the conference hall in his absence as he led another insurgency in Bolivia – outlined the nature of the solidarity to be forged between the gathered revolutionaries: “It is not a matter of wishing success to the victim of aggression, but of sharing his fate; one must accompany him to his death or to victory.” He asks his audience “what role shall we, the exploited people of the world, play?” to which he responds with the famous call – “create one, two, many Vietnams.” If Guevara set out the tricontinental vision of solidarity as a coordinated action, Amilcar Cabral’s contribution to the meeting addressed the need for a theoretical underpinning to this action: in particular, how to connect national liberation struggles against colonialism with a Marxist theory of revolution. He emphasized the need for the forum to elaborate an ideological coherence to the global anti-colonial movement, whilst recognizing that “national liberation and social revolution are not exportable commodities: they are… determined by the historical reality of each people.” Whilst this ideological coherence may have remained elusive to the broad movement, the search for a unified strategy fostered creative and transformative exchanges between those who came to Cuba and sought to build solidarity in their common struggles.

The Way of the Third World

Two years after the Tricontinental meeting, in January 1968, over 400 intellectuals from 70 countries arrived for the Cultural Congress at the Hotel Havana Libre, with the stated aim to advance “the development of the revolutionary ideology of the national liberation movements of the Third World.” Taking place before a growing polarization in the global Left’s support for Cuba triggered by events later that year, the gathering marked a high point of the tricontinental spirit. The congress, in its deliberations over the role of the intellectual in the anti-colonial movement, aimed not just at expanding the scope of intellectual production, but also at re-conceptualizing the intellectual as one that combined thought and action in worldmaking, in opposition to the character of the academic or professional specialist produced by the capitalist West and detached from the popular struggle. This was an intellectual activity derived from a belief in the possibility of changing the material world in which they lived, inspired in many ways by the Cubans who themselves represented a revolutionary culture of hope.

For the writer C.L.R. James, whose presence at the congress was his first visit to the island, the gathering marked the end of one era and the opening of another, adding the Cuban leader to the list of those responsible for paving an alternative path: “The world ushered in by Christopher Columbus and Martin Luther no longer exists. Lenin, Gandhi, Nehru, Mao Tse-tung, Nkrumah, and Fidel Castro have shattered its foundations.” Aimé Césaire, the Martinique anticolonialist, declared to the meeting “Cuba has invented a new way that will be the way of the Third World… you start from zero and you create.” He elaborated on the special quality of the revolutionary in this context – as one dialectically driven to act from the perspective of the future, engendering a dynamic that advances reality, in such a way that “they appear to belong to a world that does not yet exist.” From this perspective, he explained, even the perceived ‘failures’ of leaders like Guevara – who had by then been assassinated in Bolivia – act as a major catalyst for revolutionary transformation, in so far as their actions make manifest in the present the ideas of the future.

The gathering’s attendees – poets, doctors, lawyers, militants, scientists, actors – mirrored this conception of the worldmaking intellectual. Present amongst them were numerous speakers from the Arab world, including Gisele Halimi, the Tunisian lawyer famous for defending members of the Algerian Front de Libération Nationale (FLN), who presented a paper on how to build cultures of emancipation against imperialism, and Dr. Galal A. Amin, the Egyptian economist who spoke on the role of the university in relation to revolution. From the outset, the Cuban revolution’s internationalist imagination had extended to the liberation movements of the Arab world, with assistance to the Algerian revolution – in the form of arms and doctors – one of the first acts of Castro’s foreign policy, motivated by the ‘spontaneous brotherhood’ that existed between their struggles. The 1967 June war – understood as a setback for the Third World project as a whole – had focused Arab and international revolutionary attention on anti-imperialism in the Middle East, with Fatah emerging in the aftermath of the Arab armies’ defeat as the new front of the struggle. Fatah, who had already produced pamphlets studying the Cuban revolutionary experience, sent its representatives to the Cultural Congress to highlight their integral role in the Third World struggle. Discussion at the congress focused on the Zionist occupation of Palestine and the role of the tricontinental movement in advancing Palestinian national liberation. The collective voice of the meeting called for the integration of Palestinian liberation into the revolutionary ideology of Third Worldism.

Support for the Palestinian struggle would feature increasingly in Cuban internationalism: in the cultural and intellectual production of OSPAAAL, in the activities of Cuba in international diplomatic forums, and in the invitation of delegations to the island. Following Cuba’s break of official ties with Israel in 1973, in 1974, Yasser Arafat made his first visit to the island, and the permanent Palestinian diplomatic office was established in Havana. The same year, the Second Congress of Cuban Women turned its focus to the international struggle, receiving delegations of activists from a number of national women’s unions, political movements, and the International Democratic Federation of Women (WIDF). May Sayegh, head of the General Union of Palestinian Women (GUPS), traveled to the island to take part in the meeting. She participated in a press conference, told the audience the history of the Palestinian struggle, and made the call for renewed and increased solidarity with the liberation of her people. Sayegh formed a close friendship with Vilma Espín, the leader of the Federation of Cuban Women (FMC), and the two worked together to transform the international institutions charged with advancing the position of the women of the world. Their aim to get more women from Africa, Asia, and Latin America elected to leadership positions within the WIDF, so they could shape the agenda not just participate in it, was successful, with Sayegh herself later elected as Vice President of the organization. In their collective efforts to transform, rather than simply join, the political institutions of the era, the women successfully promoted the interests of the national liberation movements and struggles of the Third World on the international stage.

Ruptures and Traditions of Revolutionary Transformation

If the high point of tricontinentalism can be located in the late 1960s to the mid-1970s, in the years that followed the international infrastructures and networks of diplomatic and financial support that held together the global anti-colonial movement came under increasing pressure. Institutions such as the WIDF became defunct by the mid-1980s, with funding and participation significantly reduced. In the historiography of anticolonialism, the worldmaking potential of international solidarity is generally recognized to have collapsed, as the pitfalls of postcolonial independence and a global counter-revolution shattered and reshaped political frameworks and hierarchies of global interaction. Within the global Left, a sense of defeat and pessimism grew to characterize the networks of optimistic collaboration that had structured the high point of anti-colonial solidarity.

For Cuba too, international disillusion with their revolutionary model increased and reached a culmination following Cuban support for the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. When Castro was elected head of the Non-Aligned Movement in 1979, following a long-run campaign for leadership, the organization of the states previously loosely allied around an opposition to imperial intervention and domination was polarized to the point of paralysis. However, despite the closure of institutions – such as OSPAAAL in 2019 – and the collapse of official networks, the Cuban model of revolutionary transformation through education has continued to present an alternative to the futures of imperial despair heralded by the collapse of a coherent Third Worldism.

As with the understanding of the intellectual at the 1968 Cultural Congress, Cuban internationalism extended a conception of education premised not only on the accumulation of knowledge but also on the application of that knowledge to advancing revolutionary society. This vision took form in the extension of invitations through scholarships to students from across the tricontinental world to study on the island, beginning in the 1960s. The philosophy behind the granting of these scholarships and the reception of students was that they use the training they received on the island by contributing to the revolutionary development of their home countries.

In her book, Crusades of Love, Regla Fernández González, Chief of the Political Department of OSPAAAL in the 1970s, wrote about the students – from Yemen, Oman, Western Sahara, Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine – who came to Cuba to learn, and who made deep impressions on the Cuban people and their history. She describes the Arab students as having arrived with a deep “revolutionary consciousness” and committed themselves to political organizing on the island alongside their studies. She tells the story of Issam, the son of the leader of one of the left Palestinian organizations, who came to Cuba and immediately upon arrival took up responsibilities in the Cuban and Palestinian student unions on the island, the FEU, and the GUPS. He was eager to make the cause of his people known and would speak in meetings, conferences, and conversations about the history of his occupied homeland. Issam met, fell in love, and eventually married a fellow medical student from Cuba, Rosa. He is one of the many Palestinian students who forged strong links with the Cuban people and culture, building friendships, marriages and families that would either return to the Middle East or stay in Cuba to practice medicine, representing the tradition of educational and social exchange that connected the revolutionary struggles.

Afterlives and Futures of Anticolonial Worldmaking

To this day, Palestinian students who have received their medical training in Cuba continue to return to the Middle East to practice their profession. These students are represented in the League of Graduates from Cuba in Lebanon, the Jose Marti Solidarity Organisation, and the League of Graduates from the Latin American Medical School (ELAM) in Jordan, Palestine, and Syria. Dr. Mohammed Abu Srour, a current DFLP representative in Cuba and graduate of the Havana University of Medical Science, set up a free medical clinic in his home of Aida camp in Bethlehem. He describes this as a way of “practicing the Cuban tradition of medicine – of serving the people without seeking profit, as a way to pay back the historic solidarity of Fidel.” Other Palestinians who graduated from Cuba have been instrumental in organizing transnational solidarity campaigns, for example, the successful campaign for the release of the Cuban Miami Five, unjustly incarcerated in US prisons in 1998. This tradition of educational exchange continues in Cuba today, most visibly in the Latin American School of Medicine (ELAM), which offers thousands of scholarships each year to students from Africa, Asia, Latin America – and left political organizations in the USA – to study and practice medicine. The afterlives of the 1960s recognition that popular education was necessary for the advancement of the anti-colonial struggle, and the commitment to making this necessity practical, demonstrates the forward-looking model of worldmaking located in Cuba’s revolutionary internationalism.

Tracing the encounters of traveling revolutionaries in Havana during the 1960s and 1970s reveals a worldmaking moment that connected the Cuban revolution to anti-colonial struggles across the world in a period of global transformation, characterised by a shared determination and hope to transform categories of thought and action. Reading national revolutionary movements as part of this global history offers a transnational model of solidarity with creative collaborations and interventions, whether in the dominant concepts of intellectual production, the structures, and agendas of international organizations, or in visions of education and health. Beyond acting as an example of the possibility of success in challenging imperialist domination, Cuba’s reception of tricontinental revolutionaries transformed its capital into a global city of solidarity. For the Palestinians, it was a place where connections were built, connections that would support the ascent of the movement on the global stage, and outlast the high era of tricontinentalism, in an enduring model of reciprocal solidarity between anti-imperial struggles.

These historic practices of optimistic anticolonial solidarity may appear alien to a contemporary world not imagined or accounted for by the revolutionaries of the 1960s and 1970s, a world characterised by political languages and frameworks that have undoubtedly changed. But the traces of an earlier worldmaking remain in the institutional memories and intergenerational revivals of revolutionary forms and horizons. Researching this history, retrieving its traditions, and tracing its afterlives – of collaboration, friendship, and mutual exchange – offers lessons for the meaning of worldmaking today, as a collective practice of transformative solidarity, grounded in a shared belief in the possibility of alternative futures.

Sorcha Thomson is a Ph.D. Fellow at Roskilde University in the project Entangled Histories of Palestine and the Global New Left. Her research examines Palestinian solidarity entanglements with the global New Left in the 1960-the 80s, through the cases of Cuba and the UK. She holds an MPhil in Modern Middle Eastern Studies from the University of Oxford (2018).

-Prepared with the editorial assistance of Nishat Akhtar