Anticolonial Hauntings: The Past as Inheritance, The Present as Obligation

Elleni Centime Zeleke, Chris Moffat and Sara Salem

Anticolonial Hauntings: The Past as Inheritance, The Present as Obligation marks the first of Borderlines’ Conversations Series, which seeks to discuss common themes from books on the study of Africa, South Asia, and the Middle East by putting authors in conversation with each other. In this conversation, we discuss Elleni Centime Zeleke’s Ethiopia in Theory: Revolution and Knowledge Production 1964-2016, Chris Moffat’s India’s Revolutionary Inheritance: Politics and the Promise of Bhagat Singh, and Sara Salem’s Anticolonial Afterlives in Egypt: The Politics of Hegemony. Borderlines’ Amy Redgrave, Karim Malak, Shaunna Rodrigues, and Sohini Chattopadhyay joined these authors to discuss how anticolonial pasts come to haunt the present.

Shaunna Rodrigues: Thank you for being part of this conversation with Borderlines! We wanted to start this discussion by asking each of you to tell us how you came to write the books you did. Sara, what made you write Anticolonial Afterlives?

Sara Salem: Anticolonial Afterlives centers Egypt’s first postcolonial project and traces some of its afterlives (1950 - 2011) by thinking with Gramsci and Fanon around revolution, capitalism, and hegemony. At first, I was interested in the 2011 revolution and the question of temporality: what was particular about the crises leading up to 2011 that sparked the revolution? But as I started researching and writing, I found that the 1950s and 1960s kept cropping up, whether through the figure of Gamal Abdel Nasser and the changes he brought about or in relation to the continuing power of the military. And so over time, the book increasingly became about exploring the connections between the two revolutions of 1952 and 2011 as well as thinking about the politics of different political projects in Egyptian history and how they all are part of the story of 2011.

To explore the politics around the two revolutions I made use of both Gramsci’s concept of hegemony and Fanon’s work on dependency and capitalism. I think of these concepts through one another, which theoretically brings the canons of Marxism and anticolonial/post-colonial theory into conversation, as they have been throughout history. As Rahul Rao has suggested, I found it fruitful to think of them together, through a reparative lens, rather than as two separate or even disparate, canons.

I was also interested in how the anticolonial struggle continues to live on in the present in particular ways and how we might understand the afterlives of 1952 today - not necessarily as a trajectory in a linear sense - but more as connecting moments of time. This meant that the anticolonial moment of the 1940s to the 1960s was a major part of the story told in the book, specifically in terms of tracing the powerful political project it produced. That is what brought me to the concept of haunting, which I found to be a really interesting point of convergence in the three books [under discussion]. Especially towards the end, my book asks whether haunting, more so than hegemony, allows us to make sense of how the anticolonial moment in Egypt seeps into the present.

Shaunna Rodrigues: Thank you for that introduction, Sara. Centime, how did you come to write Ethiopia in Theory?

Elleni Centime Zeleke: Well, I wrote the book in an attic in Toronto, and I think that is an important part of the story, somehow. I spent a lot of time in this attic being quiet and not doing very much. I would just sit there and conjure the past. That meant thinking about the Ethiopian revolution and what I had inherited from that revolution. Certainly, there was a sense of loss that came with thinking about the revolution and I wanted to think about what that loss was. My time in the attic was about meditating on how the past was present as an experience of longing and loss.

I wanted to think about loss as something that cannot be vanquished. There was a relationship that I could have with loss that invited engagement with ghosts in the ways that Avery Gordon talks about ghosts: an engagement with things that were not present, but actually, bear down on me, bear down on my body, bear down on my sense of who I am in the world and so the past was present, even though it was invisible. My time in my attic was first off, an engagement with invisibility.

In that attic, I also spent a lot of time thinking about what it means to write history and how our relationship to the past is often mystified. There are these debates about whether we can go to the archive and find the past and present it as a kind of object to our readers. But that wasn't my sense of what it meant to write history. For me, to write history was to engage in the traditions of how the past is passed down to you so that the past exists as a mode of transmission, rather than just an object that can be self-evidently presented.

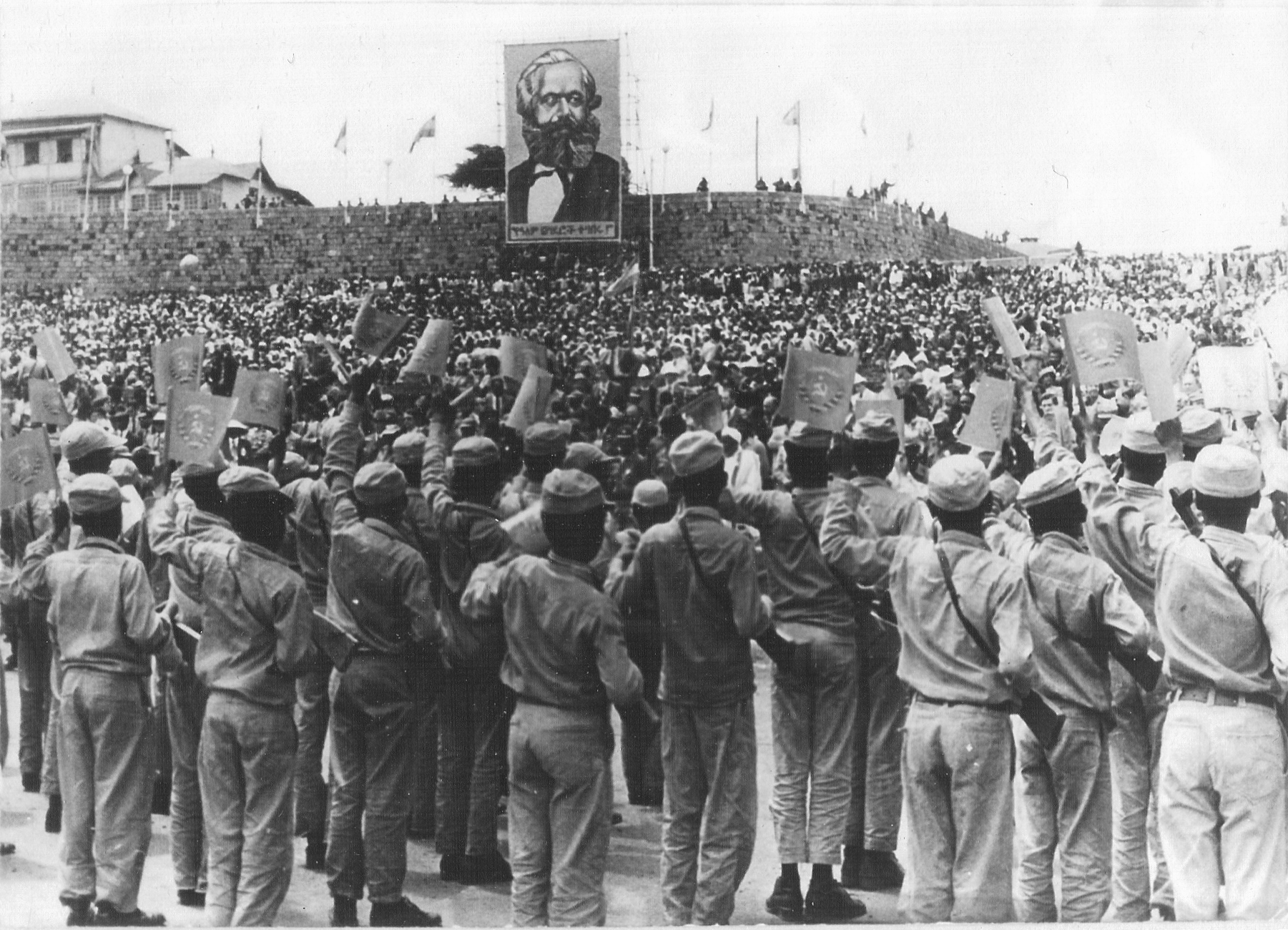

Archival reproduction 1974-1984 from the Ethiopian Ministry of Information. Courtesy of Elleni Centime Zeleke.

I call my book a memoir. I have a whole section in the book called “Theory as Memoir.” I think for me, what critical theory is doing in the book is engaging with my experience of loss, as well as my sense of the past as memory, but it is also a way to translate that memory into some kind of shared human knowledge while also submitting to the limits of human knowledge. I primarily think about the past as a web of relations that connects me to other historically situated and embodied persons. To write about the past is to talk about the ways [in which] those relationships have come to possess me in the way ghosts are known to possess a person’s body and to also think about the contingencies of human knowledge based on that possession.

I think there is some interesting crossover with what Chris talks about in his book in terms of inheritance. I'm really interested in getting into that because he talks a lot about obligation, and I talk about obligation as well. I was compelled by a sense of obligation to write my book. But I'm not sure that the obligation was coming from some kind of necessity. I think that the obligation comes out of this sense of loss, the sense of being the child of people who tried to create a different world from the one they were living in but who failed to some degree to create that world. I was interested in the gap between an attempt to create something and it's failure, and I wanted to write from that zone. Sometimes, I think that is what Marx is suggesting we do when he talks about critical practical thought in the Thesis on Feuerbach. He's talking about critique as a meditation on that gap between an attempt to make something and its failure. I think that's a project of the early Frankfurt School as well. So I situate my project in that tradition. These are perhaps all the reasons why I wrote the book. That was a very long and elaborate answer, but hopefully, it will get us somewhere.

Shaunna Rodrigues: Thank you for that, Centime. Chris, what made you write India’s Revolutionary Inheritance?

Chris Moffat: I am glad that Centime has raised this question of obligation. Because I came into the study of Indian revolutionary politics from a position of personal and geographic remove, my motivation for starting this research was not animated by a compulsion similar to that Centime describes. But thinking again with Avery Gordon, with her idea that the ghost has a determinant agency on the one who searches, I can say that the process of researching and writing this book ensnared me in many webs of obligation, intellectual and political.

The book is centered around a single figure, Bhagat Singh, who was executed in 1931 by the colonial government [of India] for conspiring to wage war against the King-Emperor. He was twenty-three years old. This young revolutionary had participated in the assassination of a police officer in Lahore in 1928 and was also involved in the bombing of the Legislative Assembly in New Delhi in 1929. His story belongs to a moment in which anticolonialism acquired the character of a mass movement in India, one that was openly breaking colonial laws and which, under the leadership of Gandhi, embraced an ethic of self-sacrifice in service of the nation. But Bhagat Singh’s life also unfolded under the world-shadow cast by the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. So, the book also relates to what Sara was saying about the global lives of Marxism and the complicated constellations that connect different contexts.

The book is not an intellectual biography of one figure. Instead, I tried to resist the desire evidenced in most existing histories of the revolutionary movement in India to uncover ‘the real’ or ‘the actual’ Bhagat Singh. I was much more interested to explore what is missed by such a narrow focus on historical excavation, and that is the vibrant and spirited domain of Bhagat Singh’s afterlives.

Recalled as shaheed-e-azam (‘the great martyr’), Bhagat Singh is widely celebrated in India today for his heroic confrontation with power, the masculine drama of his defiance, his bravery in the face of death. Rather than unpick the many myths and legends that have accumulated around him, I was interested precisely in that romance, and specifically its ideological promiscuity. Here is a figure who openly celebrated Lenin and who was involved in a republican and socialist organization, but whose specter has allied variously with right-wing Hindu nationalists, Sikh secessionists, Pakistani pacifists, and much more, haunting the entire spectrum of South Asian politics. My interest was not to say that these are ‘wrong’ ways to understand his politics but to think about what makes a figure like Bhagat Singh compelling for such a wide variety of people. What does the enduring appeal of militant commitment and self-sacrificing conviction tell us about a postcolonial present?

So, the continuing political potential associated with Bhagat Singh, so many decades after his death, was the first prompt for writing the book. The second was to think about the relationship between history and politics in the present, which is a concern all our books share. One thing I wanted to unsettle is the idea that 1947 - the year of India’s independence - represented the clear end of something and the start of a new historical sequence. If this is the case, why does Bhagat Singh remain such an effective and demanding interlocutor for the predicaments of the twenty-first century? Why is it that anticolonial histories remain so disruptive in an ostensibly postcolonial present? How do we understand the active senses of responsibility, of debt, of obligation, that binds the living to the dead?

“INHERITANCE AND HAUNTING”

Shaunna Rodrigues: Thank you so much. Let us move on to the common themes among the books. Chris, do you want to introduce what you thought were common themes in each of your works?

Chris Moffat: I can. If we're all interested in afterlives in different ways, the one concept that I'm particularly concerned with is inheritance. I understand this not as a simple logic of succession but as an untimely interference. It provides a language for understanding that sense of responsibility to something which is no longer present, which no longer exists in a physical or living form. I think inheritance captures this effect of what I call in the book a ‘malady of historicism’. By this, I don’t mean ahistoricism, nor anti-historicism, but an experience that is still very much connected to the passage of time, from past to present and on to future. I mean that experience wherein something that is supposed to be over and done with appears, in fact, to be very much present.

Bhagat Singh provides a convenient focal point for my exploration of the politics of inheritance. He stares concertedly into the present from his famous portrait, a photograph taken in 1929 before his arrest, trilby hat, and mustache, calling his inheritors to account. The fact that he died so young preserves some of his peculiar promises. The politics of inheritance takes a different form in Centime’s wider focus on an entire generation of Ethiopian student activists, their experiences of exile and the way the same figures navigate dramatic structural changes, and then another in Sara’s account of Egypt’s extended, uncertain interregnum.

Chris to Sara: I was interested to ask Sara about the unfulfilled promise of Nasserism, and whether it is invested in Nasser himself. Sara, you have this image in your last chapter of Nasser’s portrait in the back of an automobile in Cairo. How important is Nasser as a figure who holds the living to account? Are there any equivalent figures from the history of Egyptian communism, whose sacrifices haunt the present and help constitute what you call - following Stuart Hall - a disorderly domain of myths and passions here.

Sara Salem: When you said the word inheritance, what came to my mind was the idea of it being very fragmented, an incomplete or discontinuous inheritance. That is something I've been really interested in: how the inheritance of decolonization or anticolonialism is not as straightforward as we might want it to be. It is also a contradictory inheritance, in that there seems to be a struggle around grappling with what took place during decolonization, and how to make sense of it. Looking at memoirs, for instance, you can see how leftists who were active during that moment, whether in Egypt or elsewhere, spent a lot of time trying to understand what their role was in the outcome of the post-colonial era, and in relation to what went wrong with the post-colonial state.

I think in terms of your question, Chris, about Nasser versus Nasserism, there is something particular about Nasser the figure that was obviously important to the story [of Anticolonial Afterlives]. When you talk to a particular generation who were active or who grew up during the moment of decolonization, he is a figure who is evocative for many people. In Egypt today, even where there is a disavowal of him, it is often a very strong and emphatic one.

An image of Nasser in Old Cairo. Photo courtesy of Sara Adel Hussein

Despite this, I was more interested in the project that comes up through and around him, which was partly built on the energies of what came before 1952. Before 1952, we see a growing nationalist anti-colonial movement that came together around the ultimate goal of independence. Segments of this movement were very concerned with socialist politics and what independence meant economically as well as politically, and these debates are a part of our inheritance today. It is interesting to see an increasing number of conversations today around Marxism’s Eurocentrism that ask questions such as “Can Marxism be decolonized?” Yet these don’t always take note of past moments and past conversations. These are not new questions or new debates, although they're taking place in a new context. A recent book discussing elements of the Marxist inheritance in the Middle East is Fadi Bardawil’s Revolution and Disenchantment (Duke University Press 2020).

I think another important part of the inheritance of that moment is the range of possibilities it produced. I really liked, Chris, your point about looking at what was promised rather than what actually materialized. Suddenly during decolonization, there was this opening, where political possibilities guided by global currents such as socialism or non-alignment seemed possible. This opening was brief, in the sense that the possibility of a project built around socialism seemed to close up again in the 1970s with the advent of free-market reforms and the coming apart of the postcolonial project of independent economic development and decolonization.

Here I think memoirs by politicians, activists, and other figures from that era capture the social, political, economic but above all emotional promise of the moment. One I would highlight is Arwa Salih’s The Stillborn, which is linked to these discussions through her invocation of haunting to think about the figure of Nasser. Salih was a communist active in the student movement of the 1960s and 1970s, and in this memoir, she speaks about the possibilities created in and through decolonization, as well as the sense of disappointment when the changes she and her comrades had hoped for fell apart or never materialized at all. In particular, she relates this to the possibilities and hopes around socialism as a political project, and how the beginning of free-market reforms marked a point at which these possibilities seemed increasingly impossible.

Chris to Centime: Centime, as I noted, your book is not necessarily interested in individual figures - although individuals do play a role [in Ethiopia in Theory], from student leaders to political philosophers to journal editors - but rather in the unstable relationship between generations, which you allude to in your emphasis on transitions: the burden of what is inherited and also this sense of loss, which I think you capture really beautifully in that concept of Tizita.

Our use of the language of ‘inheritance’ or ‘haunting’, as opposed to that of historical ‘causes’ or even a related term like ‘legacies’, has implications here. It connects, I think, to the difference I talk about in my book, that comes from Walter Benjamin, between ‘celebrating’ the past and ‘saving it’. And here, again, the question of scholarly responsibility or obligation becomes important, vis-a-vis the work we want our books to do, how we hope they will be read.

Elleni Centime Zeleke: I try to develop the idea of Tizita as a conceptual framework for my book. On the one hand, Tizita simply means memory or nostalgia in Amharic, but it is also a genre of music, and it also refers to a musical scale. The content of a typical Tizita song always refers to lost love. An exemplary lyric would be something like: “My Tizita [memory] is you, I don’t have Tizita [memory]”. Here we see that the song refers to both the loss of form and content. Amharic is a playfully polysemic language where words can mean multiple things at the same time. What I think Tizita really allows me to think about is the ways in which we experience the past as always in relationship to the forms in which the past is given to us, but where the form itself is always unstable.

In a Tizita song, you lament both the loss of memory and the loss of the lover, the loss of form, and the loss of the experience of love. The memory of the lover can also overwhelm the container that holds the memory of the lover. Similarly, in my writing, I am trying to simultaneously think about the genres and forms through which the past has come down to me as an inheritance, while also thinking through the experience of living with the past, and it seems to me that there is actually some kind of gap between the two, always. That means that history exists at a kind of uncanny level, and it means that the past can erupt into the present in unpredictable ways. I think this comes back to the idea of the past not just as a linear movement, but as Chris says as an “untimely interference”. I think in my book I use the concept of Tizita to try to capture how the past erupts as a kind of untimely interference. And in my own writing I am also trying to capture what I have inherited from an earlier generation of people. Yet, even as I position myself as the daughter of the revolution, knowledge of the revolution is always opaque to me. It is something that I can grab at in terms of a lost love, but the form through which I know this lost love is never quite there for me. I cannot behold the lover. So, there's this constant struggle in the writing around that.

Amy Redgrave: So just thinking very broadly with this theme of inheritance, I wanted to ask Centime a question, because it seemed that in Centime’s book, one of the ways that you thought about inheritance was quite particular—in the sense that you think about the body itself as being a site of inheritance, so it is the inheritance of social and political histories, but also processes of social violence and so on. And you build on that in the book, suggesting that perhaps we could develop an alternative social science practice that is rooted in the body. So what work does that do for you conceptually, in terms of this project or maybe in your research more broadly.

Elleni Centime Zeleke: I think that I wrote the book very much against this idea that exists in African studies in particular, that you can write history as a “usable past.” I think “usable past” is a term that exists in a lot of post-colonial writing—it’s the job of the post-colonial historian or the anti-colonial historian to recover a usable past, one that could be used in the struggle against imperialism. So, we will recover this idea of African philosophy or African traditions and use it as a kind of instrument against the idea that Africans have no past or that kind of thing. And it seemed to me that this way of thinking about the past was highly instrumental and it assumed the end purpose of knowledge production before the knowledge production had even begun. So, I was really bothered by that…

I was really trying to think about another way of doing African social science or African humanities. I think that for me, there is something about the body as this place where we can pull out the universal that was intriguing to me. If the particular is the sedimentation of all the things that have happened so as to produce a particular thing, then the particular is the sedimentation of a set of relationships. The attendant sense of loss that I experienced in my body around the Ethiopian revolution allowed me to get away from rooting any notion of obligation in some kind of moralistic necessity. I needed to do this because this idea of the “usable past” is very much rooted in a kind of instrumental necessity. Instead I uncover the universal through my own body. Incidentally, I think the notion of structure of feeling, that Raymond Williams develops in his book “Marxism and Literature,” is really about capturing the ways in which even something like feeling and sentiment and affect are not just personal experiences, they are expressions of a communal experience as well. But again, by starting with my body I am starting with the situated— the situated also allows us to ask a good question rather than some kind of abstract question that is generated by a disembodied academic that could be anywhere in the world. So the usable past, in my sense, is a kind of blunt and ahistorical instrument. But when I start with my body, I am able to start with something that's situated, and this allows me to ask better types of questions.

Archival reproduction 1974-1984 from the Ethiopian Ministry of Information. Courtesy of Elleni Centime Zeleke.

Amy Redgrave: I just wonder whether this feeling that you have against the idea of the usable past, or usable history if you like, is related in some way to the particular case that you worked on in this book. You are very critical in Ethiopia in Theory about the overinvestment in the social sciences and so on that takes place in the context of Ethiopian politics. And somehow, I wondered whether your dislike of the idea of the usable past might even be connected to that critique which you develop.

Elleni Centime Zeleke: I think that the book is not just about me in my attic recovering from a certain kind of inheritance. It is also about a debate that's been happening within African Studies itself and that is centered around what it means to decolonize African studies. There are all these calls to recover an African philosophy, as you well know, or there is a call to, “Let's go back to indigenous languages.” I think that all of those debates are beside the point in many ways because they are not actually dealing with the present personal and political circumstances in which people live and how one produces knowledge in this present. No past is an object that you can just go back to and hold up and lob against the imperialists, and I think this is why the debates in African studies around decolonizing knowledge seem to be very circular to me. I think part of my book is actually about getting out of that impasse and discovering a new path. I pose the question of what it means to be a human with this particular body, in a world made by the social sciences. I do not answer that question by abstractly thinking about the social sciences, but by actually running that question through a case study with a very specific history [the Ethiopian student movement and its attendant revolution]. I propose that the question of the decolonization of knowledge production must be much more particularized. We need to run it through case studies to think more specifically about how the social sciences itself has remade what it means to produce knowledge, what it means to have relationships with others, what it means to be human.

Karim Malak: I'd like to come in on this point and think about not just the ability to regain the past or reclaim it or what have you, but also this question of afterlives itself in the literature right now.

There is great academic interest in it. But it has been discussed arguably in Arabic since the 1960s. And this is something known to Middle East studies scholars. There's the famous article by Omnia El Shakry, “History Without Documents.” She cites Ibrahim Abduh’s book in which Sadat, after Abdel Nasser, came and he burnt all the records and said, “We don't want a record of this period or to relive its legacy.” And yet that haunting has started since then, till today. And then there have been other books such as Jordanna Bailkin’s, eight years ago, about the topic of afterlives. So, I would like to think about the singularity of the confluence of afterlives across areas and disciplines and why it is now coming back to the fore.

Chris Moffat: I think there is something about the contemporary moment, an uncertainty over the status of the future, that fuels an interest in afterlives. Can we trust the future at all anymore? The rising tide of right-wing politics, the dark horizon of climate change, all these sorts of developments have, I think, informed an interest both in futures lost as well as experiences of recursion or repetition in time.

There's also something to be said about the exhaustion of memory studies, which had this big moment in the 1990s, but perhaps because of its close association with questions of trauma, mourning and reparation, its tendency toward the individual psyche, increasingly appeared ill-suited for certain sorts of analysis. ‘Afterlives’ is an altogether more capacious category, as Marlene Schäfers lays out in a recent essay for AllegraLab. It stresses the disorderly nature of the past, the way time can behave in unexpected ways, often very much out of our control, as where figures long dead interrupt the present with their call to responsibility.

How much this language helps us rethink that problem of the future, I am not sure. It is something I struggle with in my own book. Is what I’m offering, in my writing, primarily of methodological or heuristic value to readers trying to understand the power of the past in the present? Or can it go that step further, opening space to reflect on and assess horizons of political action, in league with the dead, at a moment when our futures appear to be evaporating, rarely faced with the same sort of faith in change - in the possibility of radical social change - that a lot of the people we’re studying were invested in?

Sara Salem: To me, the idea of afterlives also brings up a lot of different things. What was just mentioned - Jordanna Bailkin’s type of work on afterlives as living through social interactions and individuals - reminded me of a lot of interesting work coming out now on intimate and family histories as a means of exploring afterlives. Hazel Carby’s book Imperial Intimacies, for instance, is a compelling example of that. Then there is this growing interest—although I don’t know how new it is—in haunting. I think a lot of that has come from Avery Gordon's particular reading of Derrida’s work and how she connects that to questions of social violence that come about during colonialism and the histories of enslavement. She has a lot to say about why we become haunted at certain moments; it's not that it's a switch that turns on and off, but rather she asks us to think of what might be happening in the present that is making us feel this haunting much more intensely. This also raises methodological questions around how we understand the past in the present. The idea of haunting resonated more than the idea of legacies or (in political science) the idea of path dependency—these very formalized mechanisms where you theoretically can trace exactly how an institution, for example, is built this way because of what happened 50 years ago. I think that type of scholarship cannot capture what a lot of work around haunting is trying to look at, which is the much more subtle and ephemeral ways in which the past comes into the present, and what this means for the future.

Bhagat Singh on Progressive Students' Collective banner, Student Solidarity March, Lahore, 29 November 2019. Photograph courtesy of Javaria Waseem (instagram.com/theselfassumedartist).

Shaunna Rodrigues: Chris, what is it that is being inherited? What is it [about anti-colonial figures] that is instigating a sense of responsibility or obligation in the present? In your book, you view Bhagat Singh as not invoking an obligation to the nation or a national order, but for a normative order itself. You also say that it is not necessarily Bhagat Singh’s life or ideology that is doing this, but that it is the way he confronted politics itself which invokes a sense of obligation in the present. What kind of possibilities does that open up for how the past is making itself available to the present?

Chris Moffat: Thanks for that interesting question. Maybe I can turn it around a bit and you can all help me answer a question that is often posed to me about the specificity of Bhagat Singh’s case. The themes that I'm engaging in my work—these questions about the politics and public life of the past—connect to broader debates. But Bhagat Singh, as a figure who was executed at 23, who didn't leave much of a historical record, who was not associated with any sort of mainstream political movement, and yet who has this extraordinary popular presence decades after his death offers an arguably rare opportunity to focus on the phantasmal and spectral in politics rather than labouring to reconstruct ‘the real’ or ‘the actual’. Now in terms of your question about what is instigating the haunting, I think for me it is precisely this impression that the promise of independence, the promise of a great change in the order of things after the end of colonial rule, was not fulfilled or did not come to pass in any complete sense. In the book I invoke an early communist slogan, Yeh azadi jhooti hai or “This freedom is a lie”, to reflect this idea that 1947 was seen by many as simply a transfer of power, a change of the guard, and that the inequalities of caste, class, gender, and religion carried on or even took new forms, rather than being overturned or remedied in a way that someone like Bhagat Singh is believed to have fought for. So Bhagat Singh, bursting with potential and unfulfilled promise, becomes a signal for this unfinished business, for this struggle that is caught halfway.

I talk in the book a bit about the different ways this promise is understood. One might be this idea that a revolution was left unfinished, and that it is up to the living, today, to carry on Bhagat Singh’s fight. But I'm also interested in how the young man’s sacrifice is understood by other groups and individuals to demand a certain sort of patriotic commitment, wherein the obligation of the living is to protect this country that Bhagat Singh died for, defending it from corrupt politicians or internal enemies who threaten its integrity. This is where the dead revolutionary has been allied to a Hindu nationalist narrative. As you point out, Shaunna, I talk in the book about Bhagat Singh’s unstable relationship with normative order, so his alliances to party or nation are usually provisional and always contested. But that doesn’t mean they are not meaningful, that they do not have political effects, and the book tries to take seriously these often contradictory ways that Bhagat Singh is sought as a guide for navigating an imperfect present.

There are many figures from India’s anti-colonial history who could be said to haunt the country’s present, but I do wonder if there is something peculiar about Bhagat Singh, something related to this particular instance of youthful martyrdom and the purchase of its heroic masculinity. This relates to the earlier discussion about individual figures as focal points for a politics of inheritance. Are some calls to responsibility more powerful than others?

Shaunna Rodrigues: Centime, Sara, could you come in on the question of individual figures? What does it mean to have this conversation of haunting with individual [historical] figures versus ideologies or institutions?

Elleni Centime Zeleke: I think that the question of haunting is interesting because there is a way of doing global intellectual history that is just about finding these interesting characters in the world’s periphery and saying that they had these very interesting thoughts. I think there's a trend, especially most recently within the field of comparative political theory, to go back to the anticolonial library and to recover certain thinkers as having thought itself. It takes the archive as given, it takes anticolonial thinkers as given as well. There’s this assumption that we can recover their thoughts and prove to the Western canon that we have thinkers too. I'm wondering what haunting does for us when we don't do intellectual history in the way I just described. For me, I'm not trying to prove that Ethiopians think. That was never in doubt for me. But it seems to me that so much of global intellectual history is about that.

“METHODS”

Centime to Chris and Sara: all three of us have written books that are not interested in using Foucault to write intellectual history. I very much see haunting as a method that is opposed to the idea of presenting an archaeology of knowledge in the Foucauldian sense of that term. I want to learn from all of you what it might mean to write intellectual history in this other way where the haunting is more central.

Chris Moffat: My primary concern with Bhagat Singh as a figure in the history of political thought, as I put it in the book, was understanding how he demonstrated a certain way of being concerning the present, in relation to power. This emphasis on relationships and contingency encouraged me to think with the philosophical concept of anarchy - as distinct from anarchism as political doctrine - and this raised all sorts of problems for thinking about lineage and genealogy in any conventional sense. I was also drawn to the work of Jacques Rancière. Even though Rancière and Foucault share an interest in how dominant orders of thought and sense are established and policed, Rancière is more directly concerned with how they are disrupted - through the appearance of a dispute, the refusal to inhabit allocated roles, and so on. Understanding how such disruptions or disputes, even if they are limited or unsuccessful, can come to haunt formations of power and order that come in their wake is, I think, a compelling way for haunting and intellectual history to come together.

Poster of Bhagat Singh hanging in Bradlaugh Hall, Lahore. Photo courtesy of Chris Moffat

Sara Salem: What I found interesting about Gramsci when I first started reading him was how he understands the centrality of ideology, ideas, norms, and values to the study of materiality, and in particular his guidance on how we might position intellectual debates in relation to various social forces within society. This pushed me to think more carefully about Arab socialism in particular; is an intellectual genealogy of this current enough to capture its varied meanings, or can we also think more extensively about how it's being evoked, how it's being cultivated and constituted through these projects that made use of it, that debated its tenets, and so on.

[To Centime] I really liked it when you say in your book that you were unconcerned with whether the students you studied were good or bad Marxists, which is a debate many Marxists are still having about the Global South. Trying to answer that question with regards to Marxist strands in Egypt seems to miss what it was these forms of ideology were doing. Arab socialism was carrying out a lot of political work for Nasserism as a political project (see for instance Nazih Ayubi’s Overstating the Arab State on Egypt during the 1950s and 1960s). That seems more interesting to look at than tracing the debates over whether it was really a socialist project or not. I think that a question I had, especially seeing as how we all use haunting via Avery Gordon, is: what is it about haunting that speaks to you, and how do you think about it methodologically? This is something I've been thinking about.

Elleni Centime Zeleke: I don’t think I’m interested in recovering the past as a set of incontrovertible facts. I’m more interested in the past as something that lives in the present and that performs something that bears down on people in a particular kind of way, that activates relationships in the world. I’m more interested in those relationships. When people read my book they think it's going to be a history of the student movement. There’s this expectation that my book is going to offer very practical and useful lessons. In African studies one is always supposed to have practical solutions for things because, you know, all those poor people in Africa need solutions. But I don’t really offer obvious solutions. I try to think about history in terms of how it's lived among different groups of people with different narratives and so on.

I had an encounter when I was doing fieldwork in Ethiopia and it was with an interlocutor, somebody who had provided me with a lot of documents and a lot of anecdotal information about who did what during the student movement. One day I was hanging out in her garden with the lemon trees and the pomegranate trees and so on and she showed me a bunch of documents that would be considered “very worthwhile” for my project. And she said to me that she was going to sell these documents in the second-hand book market in Ethiopia. She was rather broke and she didn't want to hold onto the past in this way where all these books were weighing down on her. Besides she needed medicine because she was diabetic and she needed to get money for insulin. There was a part of me that was very much interested in obtaining these documents. I wanted to collect them because I thought they would help me prove the truth about the past. But she insisted: “I have to sell these things and I don't really care what happens to them. You're not going to buy them either.” That experience of letting go of “an archive” was really instructive for me, because I think there was something quite deliberate about what she was doing—she was saying that there is no truth in an archive. And she wanted me to struggle a bit more with the past than simply having access to a set of documents. And so there was actually some kind of deliberate silence that she was creating in that moment that has been powerful for me in terms of how I've written my work subsequently. She demanded a different way of approaching the past. And partly that had to do with her own economic poverty as somebody who was disappointed by the major social movements of the 20th century, which in her actual life didn't really amount to very much. I also think it was her poverty and her sadness that demanded she block any easy access to the past. So the question of haunting is about relationships for me rather than the past as an object that I can recover.

Chris Moffat: That's really interesting. And I would say the same; that I would think of my research or my project as concerned with history in the present and how it inflects and structures a whole range of relationships. We've been talking about these common reference points and I wanted to raise another point about method. Though I was inspired in my work by ethnography, I am not an ethnographer and don't really put myself in my text in a way that Centime, for instance, does at least in the opening bit of her book. But I was curious about how our relationships to our topics are rendered in our writing. Centime, you mention at one point [in Ethiopia in Theory] that you did conduct interviews, but that you didn't want to cite them or discuss them, really. You have also just shared this fascinating fragment from your research process. Could you say a bit about why that would not come into the book in some way? And Sara, similarly, I presume that you are engaged in all sorts of different ways with Cairo and with Egypt, but these connections are never made explicit in Anticolonial Afterlives. I wondered if there was a conscious decision that was maybe methodological or disciplinary, or just personal, that you didn't write yourself in, in the same way?

Elleni Centime Zeleke: I have a sense of shame doing interviews. And it's a shame that comes from going to people and trying to discover something about them, demanding that they give me nuggets of information. Often, doing interviews has felt like the replication of the apparatus of colonial knowledge production. Earlier, when I was talking about this woman who gave me a lot of documents I was saying that our relationship was primarily about hanging out. I suppose I could have written that I hung out with this woman and she gave me all of this information—but even that felt very objectifying. What happened was that at some point I was more interested in the ways in which the past comes down to us, rather than going and finding the past somewhere. And I think my refusal to objectify the answers of my interlocutors was about me situating myself within a context and thinking again about my relationality to this whole project of mine. So, driven by shame.

Chris Moffat: I mean, if it's a productive shame...

Elleni Centime Zeleke: Yes, I made it productive. I suck at conducting interviews, but I'm really good at hanging out with people. I'm really good at listening to people. And that juxtaposition was interesting for me. Why do I feel very comfortable listening and hanging out but not interviewing people? And that tension forced a shift in my project.

Amy Redgrave: I want to jump back a moment to the experience that Centime shared about her encounter with this lady and her observation that the archive in some ways, didn't particularly matter to this lady from her own positionality in the present moment and circumstances in the present moment. And I was just thinking about that in relation to this idea of afterlives. If you go back to Ethiopia in 1967 say, but whatever [other] context [too], different people, different sections of society would have had very different visions of how they wanted the future to be. Some of those would inevitably be silenced in the archive, and politically, in favor of the other trajectories which came to be dominant. What were the other kind of political imaginaries that became silenced in favor of scientific socialism?

Elleni Centime Zeleke: I mean, I'm sure there's a myriad of political trajectories that were silenced. One of the things I do in the book is show how even in 1974, the Ethiopian revolution was contested. There's lots of different ways of interpreting it. Those different interpretations are part of the tapestry of the present. This idea of haunting for me is not an instrumental method. It is actually just about how the past lives on in different relationships and in different people and institutions and archives, and is always weighing down on the present. For Marx, Benjamin, and other Frankfurt School figures, if you take yourself seriously as somebody formed by changing historical circumstances, then the self and the present is never complete. The past is an uncanny resource for renewing the present.

I wonder if part of what I'm trying to talk about is listening to silence, which is not about recovering paths not taken, but is actually about a way of writing about the past that allows for silence to be heard. I think that's what my interlocutor that I described earlier was insisting on when she denied me access to her archive. There is a way of writing where you can listen to the silences of the past by juxtaposing different modes of transmitting the past. Something emerges in that juxtaposition that cannot speak directly.

The Tiglachin monument, Addis Ababa. Archival reproduction 1974-1984 courtesy of the Ethiopian Ministry of Information

“SPACE”

Sohini Chattopadhyay: Chris, Bhagat Singh as an individual, has not really been integrated into urban historiography. But in the way you bookend your project, I think you were thinking about the urban and Bhagat Singh together. Is Bhagat Singh memorialized in the way you suggest because he cannot really be rooted to certain forms of spatial politics? Is it because we can think of Bhagat Singh’s iconography as spread across, something that blurs the rural-urban boundary, a category that we have inherited from the colonial and post-colonial sociological state? How would you place Bhagat Singh in urban history, if at all? Sara, Centime, how did space feature in your work?

Chris Moffat: Thanks, that's really interesting. It is slightly amusing to me that you say he's not engaged with urban history directly, since one of the older, doctrinal Marxist criticisms of Bhagat Singh was that he was too urban, that he didn’t engage enough with the rural struggle and the actual conditions of peasant life, where revolution was destined to come from. But that is again the question of “good Marxist or bad Marxist,” or “Was Bhagat Singh a Marxist?”

In terms of how I've treated his relationship with urban history and with place-making: this is most pronounced in how I write about Lahore, which was the city where he lived his political life and was executed in 1931, but which in 1947 became part of Pakistan. So you have this really interesting process whereby, because Bhagat Singh is seen as part of an Indian struggle and Indian history, he is extracted from this important, localized context and allocated to a new national space [in post-Partition India]. As you say, he's kind of nationalized and not really connected to a particular city, although he's definitely associated with rural Punjab still, even if the village that he was born in is also now in Pakistan.

In Pakistan, you have this really fascinating process whereby there's no official commemoration—he's not part of that national narrative of Muslim struggle—and yet you have this very lively local culture of, I wouldn't say remembrance, but collective conjuring. I discuss this in my book in reference to the street theatre in contemporary Lahore, and how Bhagat Singh is invited to occupy public space in these non-monumentalizing ways, with activists and performers disrupting the usual flows of commerce and life in the street to tell a story about a revolutionary inheritance. Such performances, usually on the revolutionary’s death or birth anniversary, force people to confront a repressed history in different ways. I concluded the book with the observation that commemorative events for Bhagat Singh in India have become almost routine: so ubiquitous, so normalized, that such celebrations can appear evacuated of any radical potential. But in Pakistan, where his presence has been repressed or resisted by the powerful, celebrating and commemorating the revolutionary remains a properly disruptive and potentially dangerous act. So, there is an important point raised through your question regarding the relationship between afterlives and place, but also, as you say, this nationalization of popular figures who become deterritorialized by necessity.

Sara Salem: I think that question of space is really interesting. I grew up in Zambia and I always wondered how and why Lusaka's main road came to be called Cairo Road. I wonder if it goes back to this moment of decolonization that produced this practice of naming roads, buildings, and so on after an anti-colonial figure from a country very far away. That's an interesting form of connectivity that is tied to space.

Elleni Centime Zeleke: As a writing project my book started as an essay that was published in Callaloo, which is a journal of African diaspora writing. The essay was called “Addis Ababa as Modernist Ruin”. It's just me walking through Addis Ababa and thinking about these layers of history that exist in the city and where I try to excavate those layers of history to think about the afterlives of the revolution. My new book is going back to urban history—that's very interesting, Chris, that we’re both going back to think about urban spaces. There's this passage in “Invisible Cities” from Italo Calvino where he asserts that nothing ever disappears if you know how to read the city. I suppose that my new project is an attempt to think about how to write the history of Addis Ababa with the idea that nothing ever disappears. In the new book, I'm just looking at one neighborhood that was established at the same time that Addis Ababa was founded in the late 19th century. I want to make the proposition that I can tell you the history of the world from this one neighborhood by recovering the sediments that make this neighborhood what it is. But I also want to insist that those sediments are everywhere. They are not hidden in documents and archives. I think this goes back to the idea of my body as this thing through which I can pull the universal out; how do I pull the universal out of this one neighborhood as well? You know, there are neighborhoods in Addis Ababa with nicknames like Chechnya. It's really interesting how ordinary people localize the international—that they're going to name their own neighborhood after a war zone very far away as a way to link their own sense of disaster with something larger.

“AFTERLIVES”

Karim Malak: Can I recast this question of afterlives across all three regions? It seems to me that on that idea of shame, Centime, there is a disavowal. Vital to this disavowal is the making of the subject matter into an object. The disavowal of creating an archive, disavowal of tracing lines. And I think that speaks to the heart of the concept of afterlives or the afterlife. But in the same way, I think we've spoken very little about those incommensurable moments. What does it mean to draw that discontinuity? What does it mean when there cannot be an assumption of what one is reclaiming and rediscovering? But I was struck that the moments of disavowal and incommensurability weren't there in your books, especially in Sara and Chris’s work, even though it's at the heart of the idea of haunting. There is something that is repressed, such as the archives of the Nasser era that were burned. There is something that isn't there, but its afterlife lives on? That's how Marx used it when he evoked the idea of haunting. I was wondering how that really informs each of your works.

Elleni Centime Zeleke: I will say I only use the word afterlives once in my book and that's in the first paragraph of the book. I did so to signal that my book is concerned with themes that one might associate with the literature that comes under the rubric of afterlives, but it's not a concept that truly animates my work. I do think that afterlives, as a term, has a sense of chronology that I wanted to stay away from. I think that the way that I was trying to write the book is constantly paying attention to disavowal.

Chris Moffat: Karim, I would actually argue that incommensurability is at the center of my book, in my interest in the excess created at the interface of sacrifice and politics, and in my attachment to anarchy as I mentioned earlier. It is also there in my refusal to make a judgment on ‘the real’ Bhagat Singh, or ‘the correct’ way to understand his legacy, which can certainly be seen as a disavowal of sorts, and has been a point of frustration for many friends reading the book.

But I do think that sensitivity to afterlives pushes us, or compels us, to question that notion that the past can be known in this stable way. Afterlives do come with a sense of chronology, as Centime says, but it is a broken, erratic one. Learning to navigate it, grapple with it, poses huge challenges for us as academics in how we think about writing, how we think about the archive. But it’s also really productive, requiring this constant, critical positioning and continual reassessment. I find that exciting both conceptually and methodologically.

Sara Salem: I think of afterlives as a way of pushing against solid notions of temporality, as well as against the idea that the past is firmly situated in the past. At the same time, the use of hegemony as a way of mapping afterlives produces a form of fixity in my book that I reflect critically in the final chapter. I think what hegemony pushes for - and some of the analysis in the book also does - is to stabilize events in a way that a framing like haunting critiques. So in the final chapter, I reflect on the narrative the book puts forward and whether more space could have been made for contradictions. Something I think about is whether haunting could move us away from this type of fixedness and perhaps towards a different understanding of afterlives.

Elleni Centime Zeleke is Assistant Professor in MESAAS, Columbia University. Her research interests include student movements in the Horn of Africa, 20th-century state formation in Africa, as well as comparative social and political theory. Elleni’s work has also appeared in the Journal of Northeast African Studies and Callaloo: A Journal of African Diaspora Arts and Letters.

Sara Salem is Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology, LSE. Sara’s main research interests include political sociology, postcolonial studies, Marxist theory, feminist theory, and global histories of empire and imperialism. She is a member of the editorial boards of the Sociological Review and Historical Materialism.

Chris Moffat is a Lecturer in South Asian History at Queen Mary University of London. He is writing a new book on architecture and history in Pakistan, provisionally titled Learning from Lahore. His work has also appeared in the Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, Comparative Studies in Society and History, Modern Intellectual History, and History Workshop Journal.